UKIPO: From Public Research Spend to Innovation: the Role of Registered IP

Executive Summary

1. Intellectual property (IP) protection is a policy instrument that aims to encourage innovation and creativity. By granting legal protection for inventions and creations, this incentivises individuals and organisations to invest time and resources into developing new ideas and products. In doing so, this helps to ensure that inventors and creators can reap the economic rewards of their innovations. IP rights also provide a framework for licensing and collaboration between different parties, thereby promoting knowledge dissemination and sharing. Overall, the aim of the IP system is to strike a balance between encouraging innovation and creativity, whilst promoting knowledge dissemination and sharing.

2. This paper examines the role registered IP protection, as a policy instrument, plays in the innovation process. This process starts with research and concludes when the invention or creation is put to use or commercialised, resulting in an innovation. Whilst other channels to innovation exist, commercialisation is the focus of this report, due to the availability of suitable data.

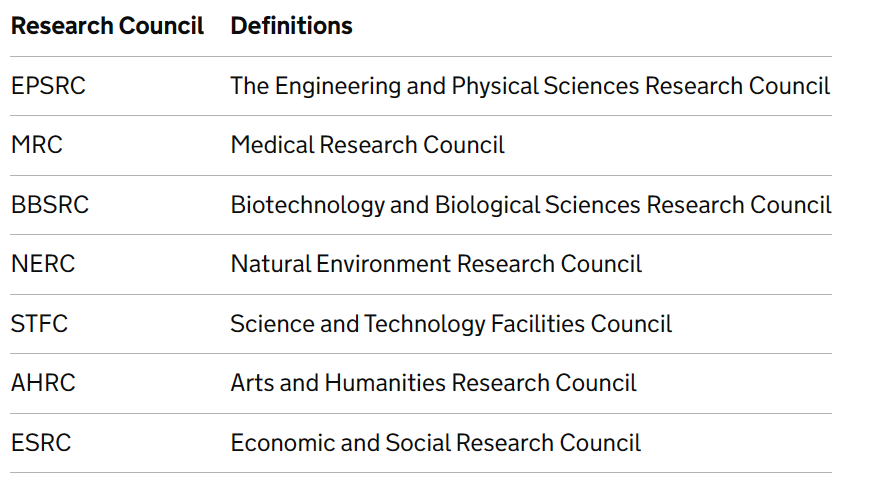

3. The role of IP in the innovation process is explored using UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) self-reported data on research council grants and their outcomes, including registered IP (patents and trade marks) and a range of commercialisation activities. Research projects in receipt of grant funding from the seven research councils between 2010 and 2020 are analysed.

4. IP and commercialisation outcomes in UKRI data are self-reported by grant recipients. Patents and registered trade marks are cross-validated against various IP data sources. Grant holders that do not complete the online reporting system risk withdrawal of future funding, however it is not possible to assess the completeness of outcomes reported, and under-reporting is possible.

5. The analysis does not extend to research funded by Innovate UK, Research England, Scottish Funding Council, Invest Northern Ireland or Higher Education Funding Council for Wales, due to differences in data collection by these funding bodies.

6. Because IP registration is a flawed indicator of innovation success, it cannot be used to measure or compare performance of research projects. Inventions that become innovations by being used are not always protected by registered IP. Registration of a patent or trade mark is not always appropriate or even possible, as evidenced by previous IPO research. Some inventors prioritise publishing their invention in academic journals, making it ineligible for patenting. Some avoid registering IP due to perceived difficulty enforcing their rights against infringers, or low risk of infringement. Some may protect their research outputs through other IPRs (copyright, design rights or trade secrets), which are not analysed in this paper due to data limitations. Others may prioritise other research outcomes; such as upskilling (particularly studentships and training grants). Furthermore, analysis in this paper shows that even if a patent or trade mark is filed for an invention, this does not necessarily mean the invention will be used.

7. Research grants awarded by the seven UK research councils) to projects that started between 2010-2020 are analysed, using UKRI survey data.

70,152 research grants were analysed, awarded to projects that started between 2010-2020, but did not necessarily complete within this date range. Studentships, training grants, fellowships and intramurals are included alongside traditional research grants

of the 37,852 research grants awarded to projects that had completed by the end of 2020, 1 in 38 chose to protect their resulting IP with a published patent application, granted patent or trade mark registration. As highlighted above, IP registration is not a good measure of innovation success. As a result, this ratio should not be interpreted in terms of innovation performance as no benchmark exists to frame this finding in a comparative context

of the patent and registered trade mark outcomes reported by grant recipients, most were published patent applications (over 80%), followed by granted patents (over 10%) and registered trade marks (4%). As published patent applications progress, the proportion of granted patents may increase in future. More trade marks may also be registered by grant recipients with projects currently at early-stage, if they progress to commercial trading in future

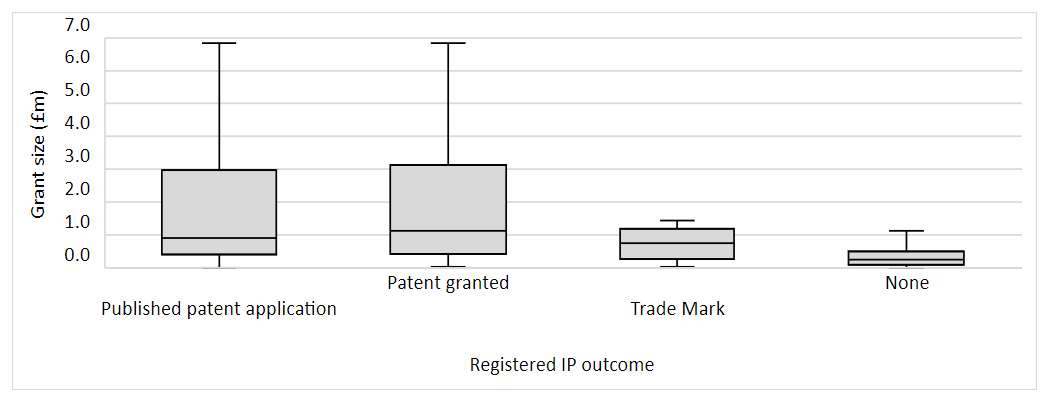

the median research council grant sizes associated with granted patents, published patent applications and registered trade marks are £1.1 million (m), £0.9m and £0.7m respectively. This does not consider further funding from other sources, such as private investment or university funds, or differences in expense across research specialisms associated with these types of IP protection. The median grant size among funded projects that did not result in a patent or registered trade mark outcome was £0.2m

scientific research projects in the fields of medicine, engineering, and biosciences (funded by MRC, EPSRC and BBSRC) were more likely to produce outputs suited to patent protection. Other types of IP protection not explored in this paper, such as copyright to protect software, literature, and other creative works, may be better suited to project outputs in the humanities and social science fields (funded by AHRC and ESRC)

from the data provided, projects led by the four universities receiving the highest research council grant funding and largest average grants also led to the most patent and registered trade mark outcomes. These universities all have mature technology transfer offices (TTOs) that are at least 20 years old and have large net current assets. These universities locate in the South East, London and East of England, impacting the regional distribution of registered IP outcomes from research council grants

8. IP rights do not imply innovation has taken place, which requires the underlying inventions or creations to be used or commercialised. This paper focuses on commercialisation outcomes self-reported by the grant recipients. Direct commercialisation by researchers is measured through the creation of spinouts, product interventions and clinical trials in the medical field, while indirect commercialisation activity is measured through IP licensing and collaboration with the private sector. It is found that registered IP in the form of patents or trade marks arising from research council grant funding is frequently commercialised (taken to market):

27% of UKRI research projects that reported a registered patent or trade mark outcome reported creating a spinout company to take forward these IP assets

40% of registered patents and trade marks associated with research council grants over the period were reported as licensed. Data is not available on licensing across the whole population of patents for comparison as rights owners are not required to provide licensing information to the IPO.

almost half (49%) of UKRI research projects that reported a registered patent or trade mark outcome were associated with private sector collaboration. Projects that reported a registered trade mark were most likely to collaborate with the private sector

17% of UKRI research projects leading to clinical trials and medical product interventions were associated with a registered patent or trade mark outcome

Introduction

Intellectual property (IP) protection is a policy instrument that aims to encourage innovation and creativity. By granting legal protection for inventions and creations, this incentivises individuals and organisations to invest time and resources into developing new ideas and products. In doing so, this helps to ensure that inventors and creators can reap the economic rewards of their innovations. IP rights also provide a framework for licensing and collaboration between different parties, thereby promoting knowledge dissemination and sharing. Overall, the aim of the IP system is to strike a balance between encouraging innovation and creativity, whilst promoting knowledge dissemination and sharing.

This paper examines the role registered IP protection, as a policy instrument, plays in the innovation process. This process starts with research and concludes when the invention or creation is put to use or commercialised, resulting in an innovation.

Innovation is a major potential route for impact of publicly funded research. The UK Innovation Strategy defines innovation as “the creation and application of new knowledge to improve the world”. The requirement for application differentiates innovation from other concepts such as invention or creation. Inventions and creations may only become innovations if they are put into use or made available for others to use. Their diffusion and uptake may then deliver value, prosperity, productivity and wellbeing. The UK Government has set the target of being the most innovative country in the world by 2030.

More specifically, this paper investigates how registered patents and trade marks, arising from research council grant funding, are translated to innovation through commercialisation channels. Whilst other channels to innovation exist, commercialisation is the focus of this report, due to the availability of suitable data. This analysis relies on the Gateway to Research (GtR) data from the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). UKRI is the national funding agency investing in science and research in the UK. Its mission is to convene, catalyse and invest in close collaboration with others to build a thriving, inclusive research and innovation system that connects discovery to prosperity and public good. The GtR dataset provides a record of IP and commercialisation outcomes self-reported by grant recipients to Researchfish, an online reporting system. It brings together seven interdisciplinary research councils that invest in research across biotechnology and biological sciences (BBSRC), engineering and physical sciences (EPSRC), medicine (MRC), science and technology facilities (STFC), natural environment (NERC), economic and social sciences (ESRC), and arts and humanities (AHRC). Grant holders that do not complete the online reporting system risk withdrawal of future funding, however it is not possible to assess the completeness of outcomes reported, and under-reporting is possible.

The sample analysed includes grants allocated to projects that started between 2010 and 2020, and may not have completed by the end of 2020. Patents and registered trade marks are cross-validated against various IP data sources.

Because IP registration is a flawed indicator of innovation success, on its own it cannot assess or compare performance of research projects. Registration of a patent or trade mark is not appropriate or even possible for all inventions. This is evidenced by results of the 2015 Survey on Innovation and Patent Use (SIPU) , which found most firms (68%) not using patent protection have inventions that are not eligible for patenting. In the UK, patent eligibility requires that an invention: (i) is new (not made public prior to application); (ii) involves an inventive step (not just an obvious modification to something that already exists); and (iii) can be made or used. Almost a third of firms in the SIPU with unpatented inventions did not fulfil the first criteria, for example because they had already published their invention in an academic journal. Furthermore, some types of inventions are simply restricted from patenting, such as medical treatments or diagnoses, scientific theories, mathematical methods, genetic processes and software with non-technical purpose. Patents can also be difficult to enforce, as reported by almost a third of SIPU respondents as a reason for their inventions being unprotected.

The SIPU found the most common reasons reported for not filing a trade mark were the presence of a pre-existing trade mark (27%), no danger of infringement (24%), and a trade mark not being perceived as important or possible (22%). A trade mark may be seen as unimportant if, for example, the owner does not intend to use their invention in a commercial setting. Some inventors prioritise publishing their invention in academic journals, making it ineligible for patenting. Some avoid registering IP due to perceived difficulty enforcing their rights against infringers, or low risk of infringement. Some may protect their research outputs through other IPRs (copyright, design rights or trade secrets), which are not analysed in this paper due to data limitations. Others may prioritise other research outcomes; such as upskilling (particularly studentships and training grants). Furthermore, analysis in this paper shows that even if a patent or trade mark is filed for an invention, this does not necessarily mean the invention will be used.

As a result, the ability of institutions to protect all possible research outcomes or IP will depend heavily on their IP protection budget and rules around filing. These parameters will change from institution to institution. Some research outputs may be better suited to protection through other IP rights not analysed in this paper, such as copyright, trade secrets, design rights or unregistered trade marks. The reader should bear this in mind when interpreting the results of this paper.

The channels through which inventions and creations are used, and therefore translated into innovation are diverse, and some are easier to monitor and quantify than others. This paper focuses on commercialisation outcomes self-reported by the grant recipients, on account of data made available by UKRI. Commercialisation is defined as “the process by which new or improved technologies, products, processes and services (arising through research) are brought to market”. For the purposes of this paper and based on outcomes reported by grant recipients in UKRI data, direct commercialisation by researchers is measured through the creation of spinouts, product interventions and clinical trials in the medical field, and indirect commercialisation activity of the research is measured through IP licensing and collaboration with the private sector.

This paper investigates four main questions to understand the role of registered patents and trade marks in translating research council grants into innovation:

How do research grant recipients protect their inventions and creations?

What types of research grant recipients protect their inventions and creations using registered patents and trade marks?

How long does it take research council grant recipients to apply for a patent once their grant is initiated?

What is the role of IP in the pursuit of a commercial route for the inventions and creations of research grant recipients?

Literature review

Several government reports have explored the role of IP in the journey from public research spend to innovation. Limited comparisons can be drawn in the results of these reports due to lack of standardisation on data collection methods, types of IP outcomes reviewed and time between research spend and data collection. The main findings are outlined below:

1. a high proportion of surveyed participants of public research grant programmes report IP outcomes, ranging from 13-42% (based on programmes that have published impact assessments)

in the Space Science Programme (SSP), 42% of 26 projects funded between 2000 and 2018 reported that IP had been achieved, including 3 unpatented ‘industrial secrets’. Grants were relatively large in size, totalling over £520m (averaging £20m per project)

in MRC’s Confidence in Concept programme, 13% of 516 projects funded between 2012 and 2016 reported a new patent application. Grants were relatively small in size, averaging £59,000

the proportion of projects associated with IP in these studies is higher than found in this report, likely due to sampling differences. The type of research funded, research objectives, grant sizes, timing of the survey, and type of IP outcomes investigated differ, and may all influence findings. This report looks only at patents and registered trade marks, a wide range of grant sizes, research specialisms (including humanities and social sciences), and grant types (including studentships and training grants)

2. mixed success of grant-holders in commercialising their IP through licensing and creation of spin-out companies:

projects supported by Research England’s HEI fund generated an estimated £7.9 for every £1 of funding 2015-2019, including through IP licensing income and spin-out creation

18% of UK scaleups that received Innovate UK grants before 2018 went on to achieve a company sale or public listing (vs 10% average for UK scaleups)

royalty-free licenses increased from 39% to 77%, 2016-2020, as a proportion of all licenses sold by UKRI-funded universities

on average, BBSRC grant holders that incorporated a spinout did so 3.6 years after receipt of the associated BBSRC grant. Most that had filed patents did so 0-2 years prior to incorporation, a finding replicated in this report for a larger dataset of grants

3. income-related measures may underestimate the impact of publicly funded research, for example:

per £1 HEIF grant 2015-2019, an estimated £2.2 was generated in non-monetised impact (e.g., royalty-free licensing and knowledge exchange through public networks)

the University of Oxford generated an estimated £4.0bn in productivity spillovers from £317m research funding allocated by UK Research Councils and UK charities 2018-2019

4. differences in IP commercialisation success are observed across countries and regions:

english and Scottish universities, recipients of the largest Innovate UK grants, had the highest average patenting activity, licensing and spinout creation 2013-2017 as reported by the National Centre for Universities and Business (NCUB)

correlation between patents granted and public R&D support is stronger in Scotland, the North and the Midlands, based on a sample of 14,500 UKRI grant holders 2004-2016. This could be related to firms in peripheral areas facing higher financial constraints, as shown by evidence of an “urban premium” in accessing credit markets

5. this paper contributes to the literature by analysing a wider sample of public research grants, namely all grants allocated by the seven research councils 2010-2020. Analysis is not limited to translational research programmes, scientific research, or certain grant types. For example, humanities research and student-led research funded by studentships and training grants are kept in the sample. This allows a more holistic picture of the types of grant holders that protect their research outputs using registered IPRs. A range of direct and indirect routes to commercialisation are investigated among the grant holders, based on their own reports

Data

UKRI Gateway to Research (GtR) data provides the main data source for this analysis, containing information on research grants allocated by the seven research councils (Figure 1). The sample analysed includes 70,152 research grants awarded to projects that started between 2010-2020, but did not necessarily complete within this date range. Studentships, training grants, fellowships and intramurals are included alongside traditional research grants.

IP and innovation outcomes are self-reported by grant recipients through the online platform, Researchfish. These include registered IP rights, including published patent applications, granted patents and trade marks, and commercialisation of research through IP licensing, spinout creation, clinical trials, medical product interventions and collaborations with the private sector.

As data is self-reported, it is incomplete and contains inconsistencies. These are mitigated where possible by cross-validation with IP data sources, including PATSTAT, the European Patent Office’s (EPO) worldwide patent statistical database, and trade mark data from the IPO and TM-Link. These sources also provide complementary data, such as patent family size.

78% of patent outcomes reported by grant recipients are found in PATSTAT, based on patent application number, the remainder are removed from the analysis. Those removed include patent applications that were withdrawn prior to publication or did not reach publication stage, for confidentiality reasons.

Just under half of registered trade marks reported by grant recipients are found in IPO data or TM-Link, the remainder are kept on account of insufficient information being provided by grant recipients for cross-validation.

Further information on the data cleaning and validation process is included in the appendix.

Figure 1: Research Council Acronyms

Results

How do research grant recipients protect their inventions and creations?

This section outlines research council grant recipients’ commercialisation use of their registered patents and trade marks. The volume and type of projects that led to these outcomes are investigated, as well as whether the registeredIPwas a patent or a trade mark, with the following results:

1 in 38 completed research projects in receipt of research council grants during the period 2010-2020, led to at least one registeredIPoutcome in the form of a patent or trade mark.Out of the 37,852 completed research projects, 983 led to at least one registered patent or trade mark outcome after receipt of funding (2.6%), generating a total of 1,357 registered patent or trade mark outcomes. When ongoing projects are included, 1 in 60 projects in receipt of research council grants led to a registered patent or trade mark outcome, generating a total of 1,543 registered patent and trade mark outcomes. These low figures reflect that the two types of registeredIPmonitored in this study are not appropriate, or even possible outcomes, for all research outputs. The sample of projects analysed is broad in research areas, grant types, and is not limited to research with translational objectives that lend themselves to patent or trade mark registration. Significant sampling differences are present compared to other studies in the literature where higher translation of public research funding toIPregistration is found. Underreporting may also be present in the self-reported data.

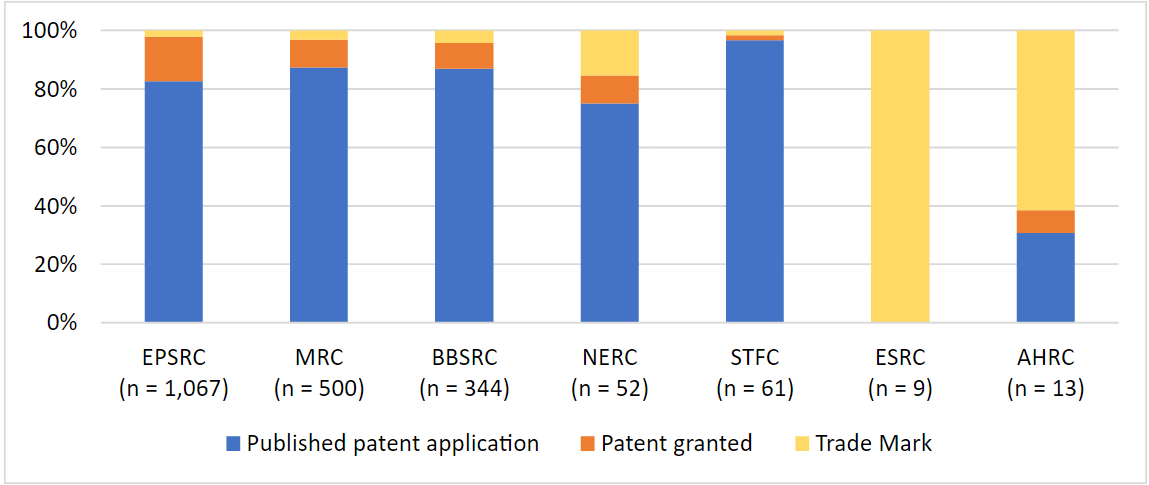

published patent applicationsmake up 80% of theIPoutcomes (published patent applications, granted patents and registered trade marks) reported by 2010-2020 research council grant recipients.(Figure 2). Published patent applications associated with more recent grants are less likely to have yet translated to granted patents

granted patents make up 12% of theIPoutcomes reported by 2010-2020 research council grant recipients.The percentage of granted patents could increase in future as more recent patent filings progress to the stage of becoming granted

registered trade marks make up 4% of theIPoutcomes reported by 2010-2020 research council grant recipients.Only 59 registered trade marks were reported. As trade marks are most often used to protect a commercial trading advantage through branding, they may be inapplicable to research that is non-commercial or early-stage. Furthermore, there may be under-reporting of trade marks that are filed by parties other than the lead research organisation, such as a licensed entity or private company acting in collaboration. The lead research organisation is solely responsible for reporting outcomes to Researchfish

research council grants associated with patent outcomes range more greatly in size than those associated with trade mark outcomes(Figure 2). The size of research council grants associated with patent outcomes is also positively skewed in distribution, meaning that a few very large grants push the average grant size above the median

the median grant amount associated with a granted patent is highest(£1.1m), followed by a published patent application (£0.9m). The median grant amount associated with a registered trade mark is smaller (£0.7m). Projects that did not report a patent or registered trade mark outcome had the smallest median grant amount (£0.2m). The analysis does not consider funding that follows a research council grant, or differences in expense of different research specialisms associated with these forms of registeredIPprotection

Figure 2: Research council grant size (£m) allocated to projects funded by research councils 2010-2020, by registered patent or trade mark outcome, shown as a boxplot

over three quarters (78%) of projects that report a registered patent or trade mark outcome also report receiving further funding from a research council, other public funding body, or private organisation.On average, projects that report a registered patent or trade mark outcome receive £8.2m further funding before the end of 2020. Most (59%) of these follow-on grants are allocated after the project’s first registered patent or trade mark outcome. By comparison, projects that do not report a registered patent or trade mark outcome receive just £1.0m further funding before the end of 2020, on average. The finding that patent holdings increase the likelihood of further research council funding is also made by Vanino et al (2019), in their analysis ofGtRdata. Further funding is not reflected in Figure 2

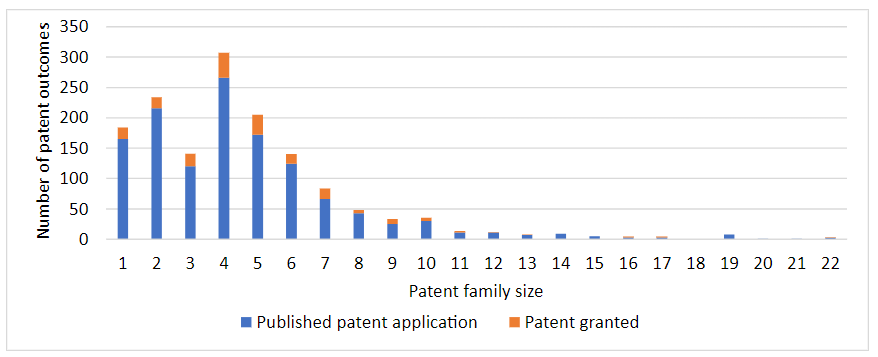

87% of published patent applications and 90% of granted patents are protected in more than one jurisdiction. The most common number of jurisdictions for patent protection sought by research council grant recipients is four(Figure 3). Patent family size refers to the number of jurisdictional patent offices where an invention is protected by a patent. It is sometimes used as a proxy for patent value, based on the assumption that rights holders reserve their more valuable inventions for international patenting given the costs associated with filing patents in multiple jurisdictions. The number of jurisdictions in which a patent is protected could also be influenced by the institution’s patent budget, licensing income, and the technology readiness level (TRL) and field of their invention.

more than half (55%) of grant recipients’ patent filings are Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) applications, providing international protection

Figure 3: Number of patent outcomes (published patent applications and granted patents) from research projects funded by research councils 2010-2020, by patent family size.

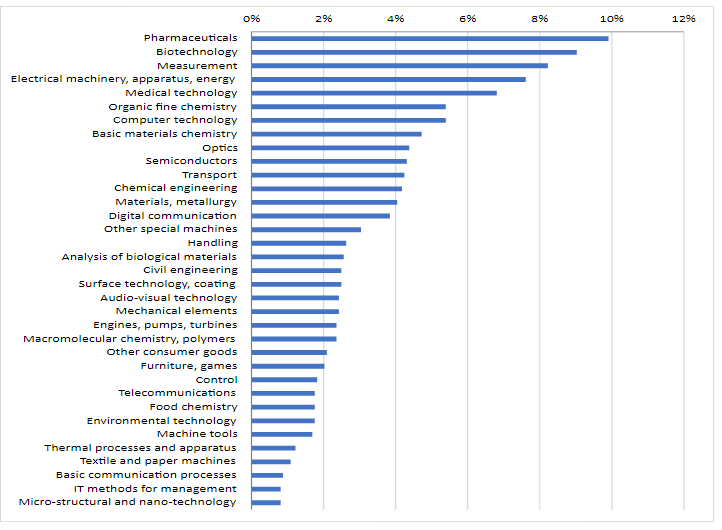

pharmaceutical and biotechnology inventions were most commonly patented by research council grant recipients(Figure 4). 10% and 9% of patent outcomes were filed by research council grant recipients in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology fields, respectively. Previous UKIPO researchhas found that these technology fields rely heavily on patenting, relative to other UK industries. Research grant recipients less frequently patent research outputs in other fields, such as data analysis, service, textiles, consumer goods, furniture, and games

Figure 4: Percentage of patent outcomes (published patent applications and granted patents) from research projects funded by research councils 2010-2020, by technology field. Patents are assigned to technology fields by patent examiners when they are published.

Patents reported by research grant holders are most frequently filed in the fields of pharmaceuticals (10%), biotechnology (9%), measurement (8%), electrical machinery, apparatus, energy (8%) and medical technology (7%).

What types of research grant recipients protect their inventions and creations using registered patents and trade marks?

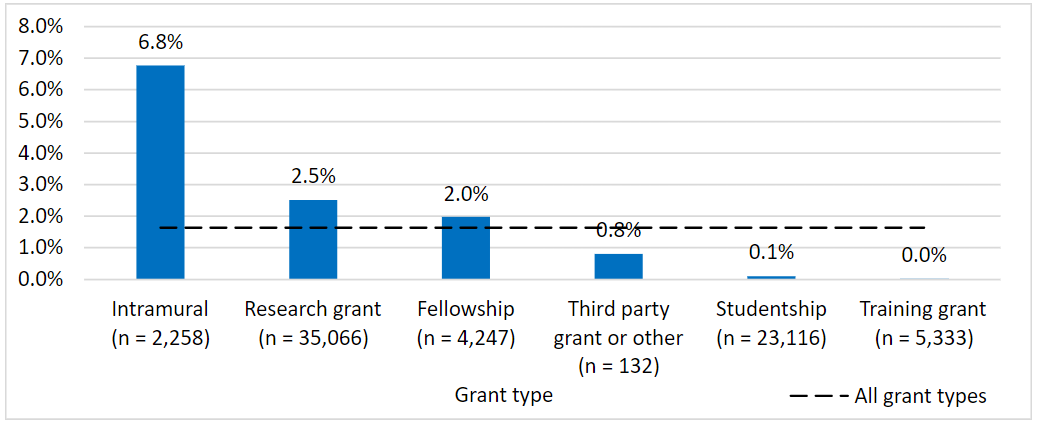

some grant types were more likely than others to lead to a reported patent or registered trade mark outcome(see appendix forGtRgrant type definitions). Intramurals, research grants and fellowships were the grant types found most likely to be associated with registered patent or trade mark outcomes. These grants support research carried out by employees of universities and research institutes. Studentships and training grants were found least likely to be associated with registered patent or trade mark outcomes (Figure 5). These support research carried out by students with the objective of leading to a postgraduate qualification. It is notable that the statistical validity of findings may be reduced by the relatively small number of projects that received intramural grants and third party grants.

Figure 5: Percentage of projects funded by research councils 2010-2020 that led to at least one registered patent or trade mark outcome (published patent application, granted patent or registered trade mark), by grant type. In brackets, n = number of projects funded by research councils 2010-2020, by grant type (grant type definitions included in the appendix).

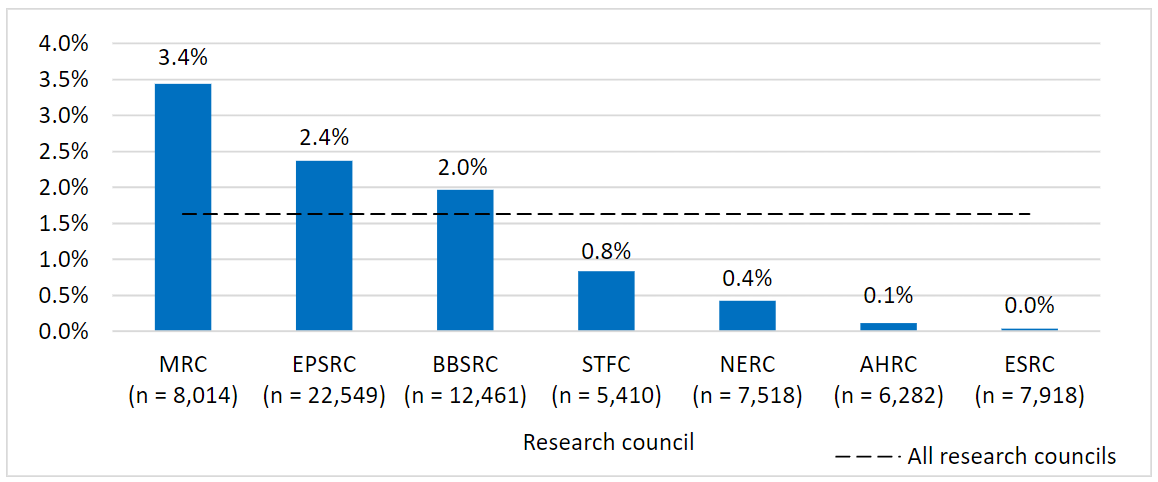

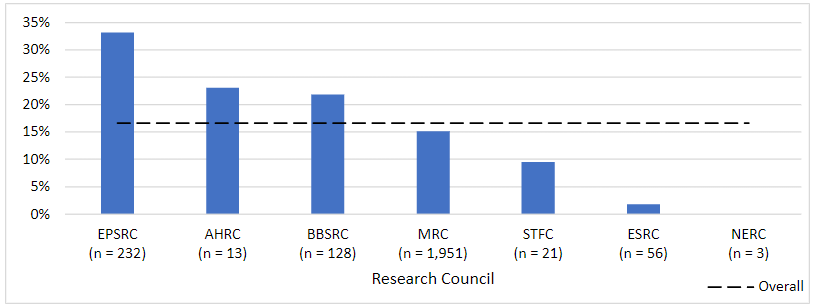

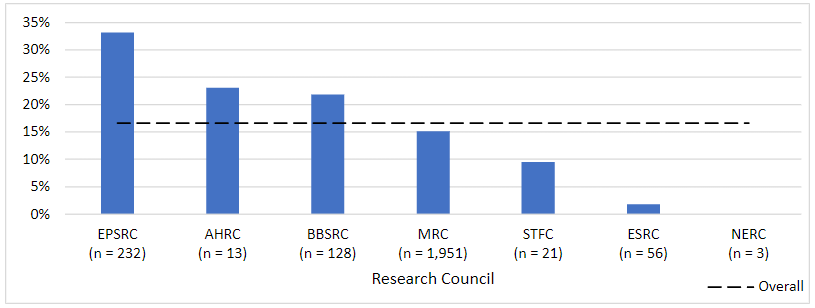

grants administered by some research councils were more likely than others to lead to a reported patent or registered trade mark outcome.Research projects funded by science-focused councils (MRC,EPSRCandBBSRC) are more likely to lead to a patent or registered trade mark outcome (Figure 6). Whereas, research projects funded by councils in the social sciences and humanities fields (AHRCandESRC) may be protected by otherIPrights not explored in this paper, such as copyright to protect software, literature, and other creative works.

Figure 6: Percentage of projects funded by research councils 2010-2020 that led to at least one registered patent or trade mark outcome (published patent application, granted patent or registered trade mark), by research council. In brackets, n = number of projects funded by research councils 2010-2020, by research council.

3.4% of MRC grants, 2.4% of EPSRC grants, 2.0% of BBSRC grants, 0.8% of STFC grants, 0.4% of NERC grants, 0.1% of AHRC grants, and 0.0% of ESRC grants led to at least one registered patent or trade mark outcome.

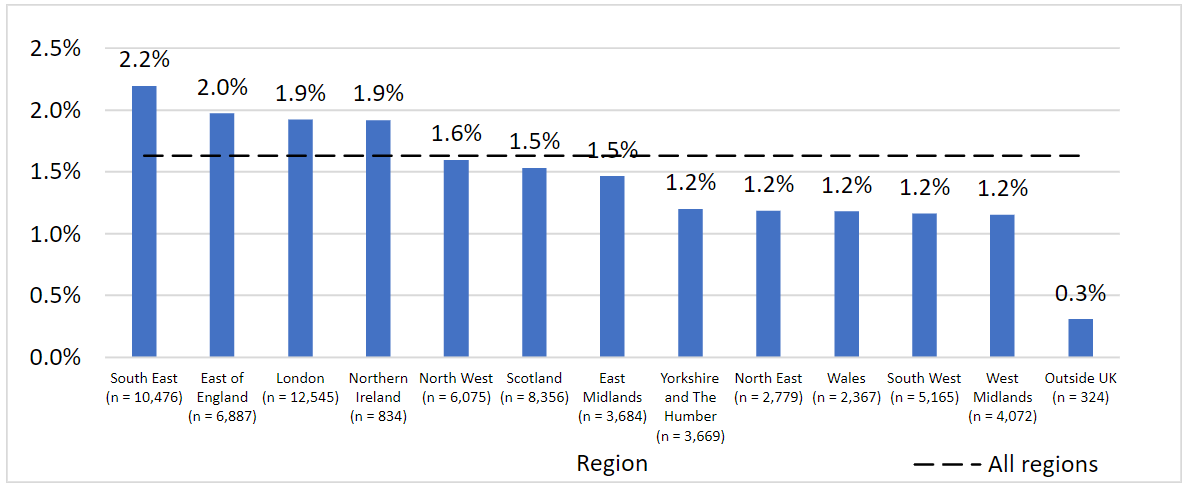

The South East, East of England and London have the highest percentage of research projects with at least one registeredIPoutcome(Figure 7), and the highest number of patent and registered trade mark outcomes overall. The top 5 universities by number of registered patent or trade mark outcomes all locate in these regions, and these regions received the most funding: almost half of total research council grant spend, 2010-2020. Other studies have also found regional variation inIPoutcomes of public-funded research to correlate with regional variation in funding size. The analysis does not control for regional variation in access to other funding sources, such as from regional funding bodies: Research England; Scottish Funding Council; Invest Northern Ireland; and Higher Education Funding Council for Wales, or private investors.

Figure 7: Percentage of projects funded by research councils, 2010-2020, that led to at least one registered patent or trade mark outcome (published patent application, granted patent or registered trade mark), by region of lead grant recipient. In brackets, n = number of projects funded by research councils 2010-2020, by region of lead grant recipient.

Of research council grants across the UK, 2.2% in the South East, 2.0% in the East, 1.9% in London and Northern Ireland, 1.6% in the North West, 1.5% in Scotland and East Midlands, and 1.2% in all other regions led to a registered patent or trade mark.

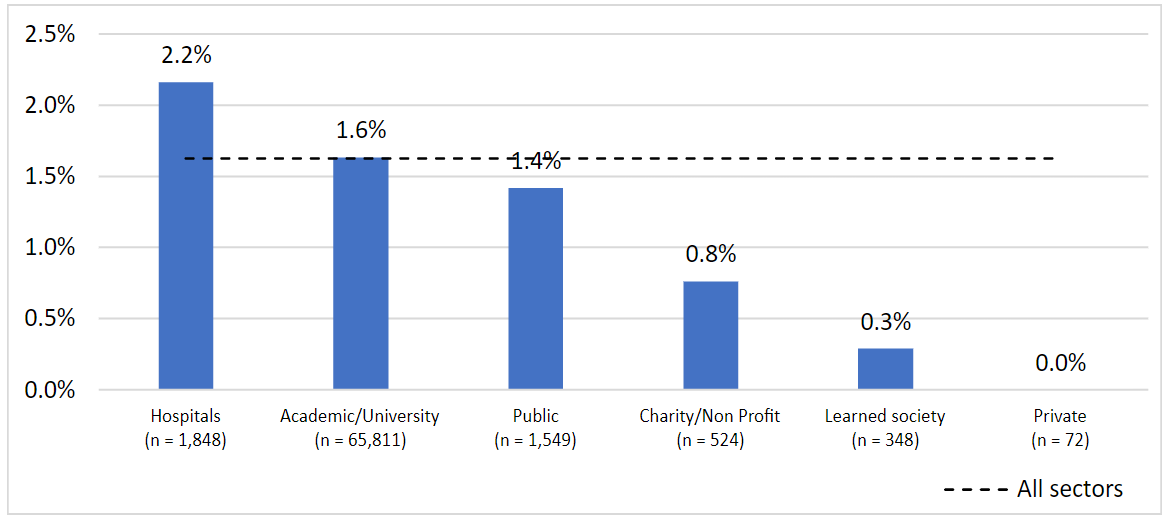

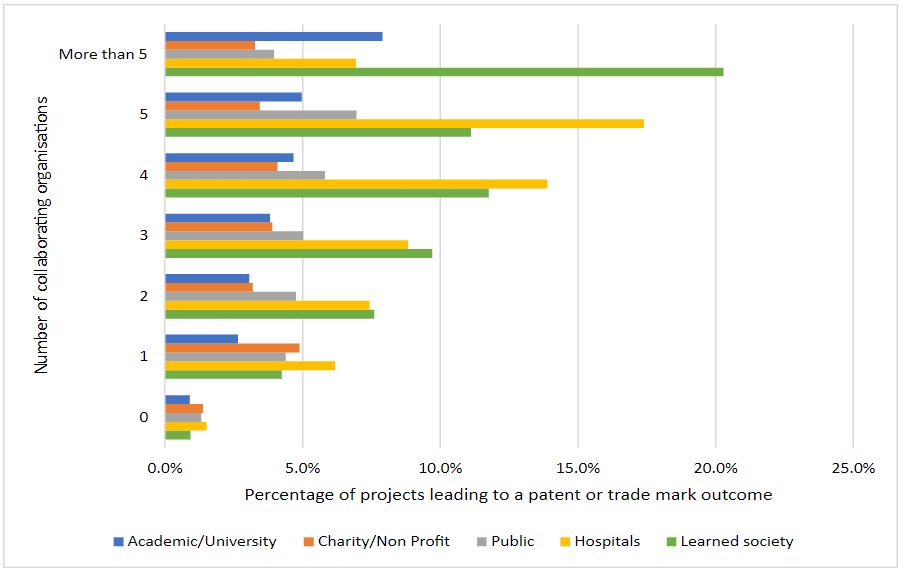

projects led by hospitals, academic/universities and public organisations were most likely to result in at least one registered patent or trade mark outcomeThis does not take into account business as usual research conducted by those organisations, specialist equipment, or other sources of funding. The largest number of registered patent and trade mark outcomes came from academic/university-led projects, which constitute 94% of projects in the dataset. Projects led by charity/non-profit organisations, learned society and private organisations (mostly social enterprises) were less likely to associate with at least one registered patent or trade mark outcome. This may reflect that charitable status limits the commercial value that can be gained fromIP, in accordance with the Charity Act 2011 and the UK’s international subsidy control commitments. The relatively small number of projects led by private companies may reduce the statistical validity of findings

Figure 8: Percentage of projects funded by research councils, 2010-2020, that led to at least one registeredIPoutcome (published patent application, granted patent or registered trade mark), by sector of lead grant recipient. In brackets, n = number of projects funded by research councils 2010-2020, by sector of grant recipient (see figure 25 for definitions).

2.2% of research council grants made to hospitals, 1.6% to academic/universities, 1.4% to public organisations, 0.8% to charities / non-profits, 0.3% to learned society, and 0.0% to private organisations led to a registered patent or trade mark.

a quarter of projects reported receiving further funding from a research council, other public funding body, or private organisation before the end of 2020.Of projects in receipt of further funding, just over 5% reported a registered patent or trade mark outcome (compared to 1.6% of all projects). Most (58%) of these had registered their first patent or trade mark outcome before receipt of further funding. Other than the research councils, the European Commission, Wellcome Trust, the National Institute for Health Research and the Royal Society were common providers of further funding

just over a quarter (28%) of projects involved collaboration between the lead research organisation and another entity. These projects were more likely to have a patent or registered trade mark outcome than projects led by only one organisation(Figure 9). 16,085 projects involved a university collaboration, 6,571 projects involved a public sector organisation collaboration, 5,653 projects involved a charity/non-profit collaboration, and 1,466 projects involved a hospital collaboration. Of these, 4.1%, 4.6%, 4.3% and 6.9% led to a patent or registered trade mark outcome, respectively

generally, as the number of collaborating entities increase, the likelihood the project will report a patent or registered trade mark outcome increases(Figure 9).However, this effect is not observed for charity/non-profit collaborations

hospital collaborations are most associated with patent or registered trade mark outcomes(Figure 9). This includes collaboration between universities and their affiliated teaching hospitals, where universities can draw upon extensive medical resources and training. Not only is medicine a particularly patentable research area (see Figure 4), but it is also an area with a wide range of alternative funding sources, including from the National Institute for Health Research and topic/disease specific charities. This alternative funding is not considered in this analysis

Figure 9: Percentage of projects involving collaborations with universities, charity / non-profit organisations, public organisations and hospitals, that led to a patent or trade mark outcome.

trade marks are the most common registeredIPoutcome among projects funded by the social science and humanities research councils trade marks are the most common registeredIPoutcome among projects funded by the social science and humanities research councils(ESRCandAHRC). Published patent applications are the most common registeredIPoutcome among projects funded by all of the other research councils (Figure 10). Different types of research generate outputs that are suited to different types ofIPprotection

Figure 10: Breakdown of type of registeredIPoutcomes associated with research projects funded by the different research councils, 2010-2020. In brackets, n = total number of registeredIPoutcomes associated with projects funded by that research council, 2010-2020.

Over three quarters of registered IP outcomes reported by EPSRC, MRC, BBSRC, NERC and STFC grant recipients are published patent applications. All reported by ESRC grant recipients, and over half reported by AHRC grant recipients are trade marks.

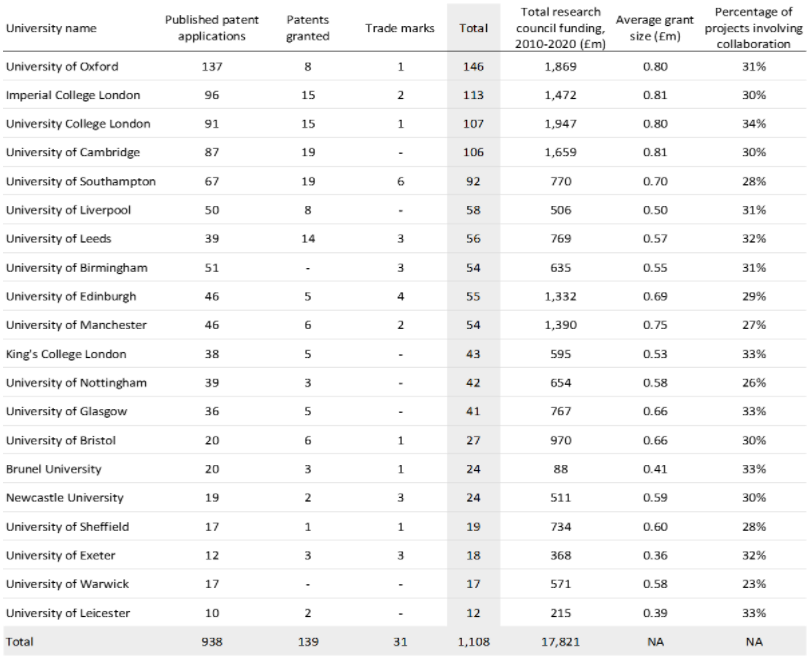

projects led by the four universities receiving the most grant funding, and largest research council grants on average, led to the most registeredIPoutcomes(Figure 11). These universities all have mature technology transfer offices (TTOs) that are at least 20 years old, with large net current assets (see Figure 32). They do not differ significantly from each other in the percentage of their projects involving collaboration (Figure 11).

the University of Birmingham and University of Southampton have the highest share of research grants with a trade mark outcome(9% and 5% respectively), all funded byAHRCandEPSRC, mostly protecting brand names associated with video software, cleaning and medical technology

some universities required less funding from research councils per registered patent or trade mark outcome.Brunel University, the University of Southampton and the University of Liverpool required the least research council funding per registered patent or trade mark outcome: £3.7m, £8.4m and £8.7m respectively (Figure 11). However, this does not reflect university performance as this analysis does not control for other sources of funding received by the universities, prior to registering the patent or trade mark

Figure 11: Top 20 universities by number of registeredIPoutcomes associated with research council funded projects for which they acted as the lead research organisation, 2010-2020.

How long does it take research council grant recipients to apply for a patent once their grant is initiated?

The time taken to apply for a patent after receipt of a research council grant is investigated among the sample of 2010-2020 grant recipients. Timing to patent is analysed across different research grant years, research councils, and grant recipients, with the following results:

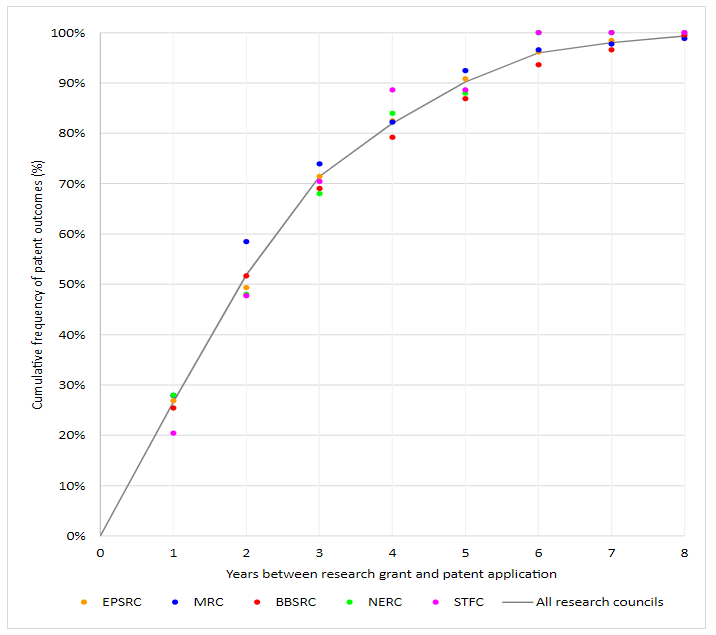

the most common time taken to apply for a patent after receipt of a research council grant is within 2 years.The percentage of research council funded projects that applied for a patent within 1 year of grant receipt was highest in the 2016 and 2017 cohorts of grant recipients. Patent applications typically take 18 months to reach publication, and only published patent applications are analysed. Therefore, more recent cohorts of grant recipients have had less time to apply for a patent, and for their applications to become published

overall, a quarter of patent outcomes were applied for less than a year after receipt of a research council grant.Further analysis is needed to see if short times taken to patent following a research grant reflects funded research being late-stage, or at high Technology Readiness Levels.

there is little significant time difference between grant receipt and patent application across projects funded by the different research councils(Figure 12), although projects funded byMRCtend to apply for patent protection slightly faster. Over 40% ofMRCgrants go to translational research programmes operating closer to market, including the Developmental Pathway Funding Scheme (DPFS) and theMRCConfidence in Concept (CiC) scheme (now the Impact Acceleration Account,IAA).

Figure 12: Cumulative frequency of patent outcomes with a given number of years between receipt of a research grant and patent application date of published patents, by funding organisation. Includes all published patent publications and granted patents applied for by grant recipients, following receipt of grant funding by one of the seven research councils 2010-2020.

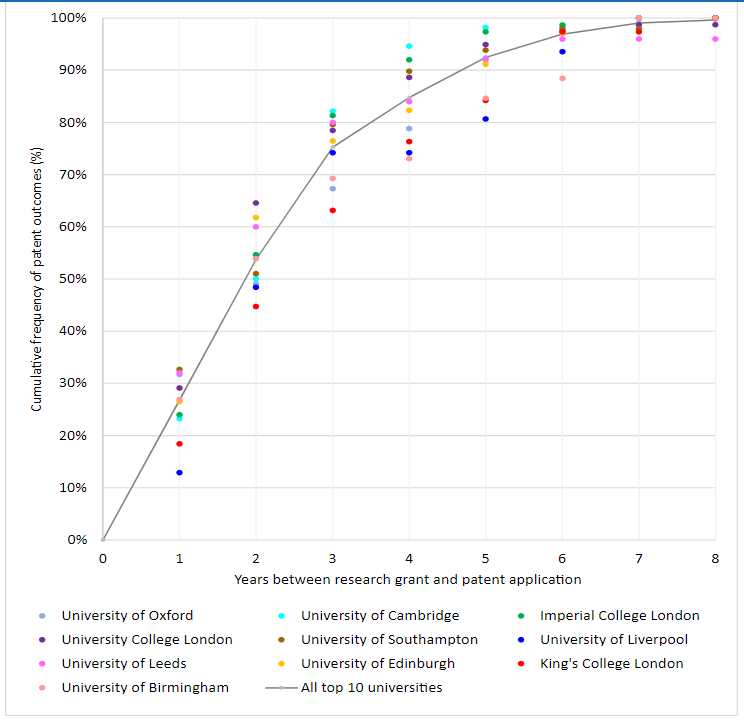

there is more variation in time difference between research grant and published patent application across universities(Figure 13). University College London, University of Edinburgh and University of Leeds tend to apply for patent protection faster than other universities. Universities’IPfiling strategies and technology transfer offices differ (see Figure 32), and they specialise in different research areas at different stages of development

Figure 13: Cumulative frequency of published patent outcomes with a given number of years between receipt of a research grant and patent application date, by university applicant. Includes all patent publications and granted patents applied for by the top 10 universities, following receipt of grant funding by one of the seven research councils 2010-2020.

What is the role ofIPin the pursuit of a commercial route for the inventions and creations of research grant recipients?

To become innovations, inventions and creations must be used, or made available for others to use. Their use may then deliver economic and social value. The relationship between registered IPRs and use ofIPis complex, with the former not necessarily guaranteeing the latter. Commercialisation is a channel through which inventions and creations can be made available for use, through bringing to market new or improved products and processes arising from research. The relationship between registered patent and trade markIPoutcomes and commercialisation outcomes reported by research council grant recipients is explored in this section.

Commercialisation can take many forms. Direct commercialisation by an inventor may involve spinout creation or clinical trials with the aim of introducing a product on the market. Commercialisation can also be indirect, if the invention is made available for others to bring to market throughIPlicensing or collaboration with the private sector, where the inventor and research team may still play an active consultancy role. The following section investigates some of these different routes to innovation among recipients of research council grants and the role ofIPprotection.

Direct commercialisation

Spinouts

A spinout is defined byGtRas any new business resulting directly from a research project that has received research council funding. These businesses may take forward projects’ inventions or creations by creating an entity to develop and market products, or licenseIP.

The incorporation of a spinout may be assisted by a university’s Technology Transfer Office (TTO) (see Figure 32). Universities also have access to other funding sources, including university seed spinout funds, external venture capital (VC) funds allied to universities or active in their spinouts, and general seed investor funds (see Figure 33), which are not considered in the analysis.

The association between registered patents and trade marks and translation of research council grants into spinouts is investigated, with the following results:

over a quarter (27%) of projects that reported a registered patent or trade mark outcome also reported the creation of a spinout company.Granted patents were most frequently associated with spinout outcomes

a total of 710 spinouts were reported by recipients of research council grants between 2010 and 2020.Based on information reported by grant recipients, of these spinouts, 279 (39%) have at least one published patent application, 86 (12%) have at least one patent granted, and 17 (2%) have a registered trade mark. This mirrors findings elsewhere in the literature: a third of spinout companies building onBBSRCinvestments were found to have a published patent application in a 2019 study. Under-reporting is possible, particularly whereIPregistration is carried out by the spinout or another third party that is not the grant recipient

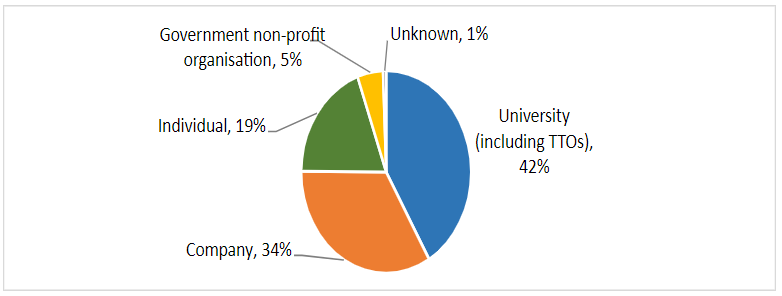

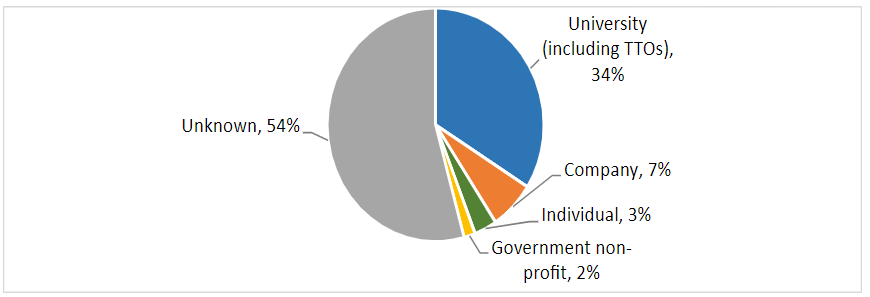

universities and their technology transfer offices (TTOs) are the most common applicants for patents and trade marks associated with spinouts that arise from research council funding(Figure 14, Figure 15). Where an application is made by the university or itsTTO, the right would need to be licensed or transferred to the spinout to allow it to use theIP. A third of patents reported by grant recipients, associated with at least one spinout, were applied for by a company.

Figure 14: Applicants of patents associated with spinout companies launched from 2010-2020 research council funding, by type (as found in PATSTAT).

Figure 15: Applicants of trade marks associated with spinout companies launched from 2010-2020 research council funding, by type (as found in IPO data and TM-Link).

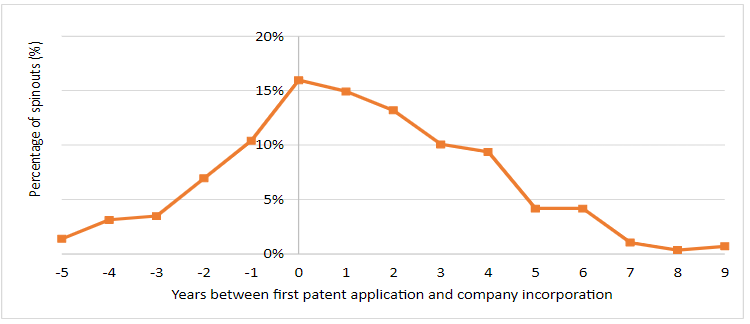

of the spinouts associated with patents, 74% incorporated after the first patent application had been filed(positive values in Figure 16). In these cases, the patent would be licensed or transferred to the spinout upon incorporation. The remaining 26% of spinouts incorporated before the first patent application had been filed (negative values in Figure 16). These early-stage companies are often referred to as “shell companies”, set up while their IP is being further developed by the researcher. These findings are in line with previous analysis of BBSRC grant data.

Figure 16: Years between patent application and spinout incorporation. Negative figures on the x-axis show patents being applied for before spinout incorporation, positive figures on the x-axis show patents being applied for after spinout incorporation. Includes all spinouts associated with grant funding by one of the seven research councils 2010-2020, that are also associated with at least one patent application.

spinouts incorporate sooner after receipt of research council funding if they do so before the associated project’s first patent application filing.Applying for a patent is a timely process that may come before or after the incorporation of the spinout company. Spinouts incorporated after a patent application incorporated 3.7 years after receipt of research council funding, on average. Spinouts incorporated before a patent application incorporated 1.2 years after receipt of research council funding, on average

clinical trials study the effectiveness of a medical invention by evaluating its effect on health outcomes. This is an important stage in the commercialisation of most medical products, as gaining approval to market a medicine (“market authorisation”) by the MHRA or FDA requires assessment of evidence obtained at clinical trial. The association between reported registration of a patent or trade mark and translation of research council grants into medical inventions adopted by the market is investigated, with the following results:

Clinical trials and product interventions in the medical field

Clinical trials study the effectiveness of a medical invention by evaluating its effect on health outcomes. This is an important stage in the commercialisation of some medical products, as gaining approval to market a medicine (“market authorisation”) by the MHRA or FDA requires assessment of evidence obtained at clinical trial. The association between reported registration of a patent or trade mark and translation of research council grants into medical inventions adopted by the market is investigated, with the following results:

a total of 2,381 clinical trials and medical product interventions were reported by recipients of research council grants between 2010 and 2020, as outcomes of funding. Of these, 396 (17%) had at least one published patent application, granted patent or registered trade mark associated with the research council grant, based on self-reported data from grant recipients

a third of clinical trials and medical product interventions associated withEPSRCgrant funding had an associated patent or registered trade mark(Figure 20).AHRC,BBSRCandMRCgrants were next most likely to have patent or registered trade marks associated with clinical trials and medical product interventions reported by grant recipients

research council funded projects involved in clinical trials are most likely to report a published patent application if they reach the non-clinical refinement stage after initial development(Figure 18). Published applications may become granted or be unsuccessful/withdrawn. Granted patents are most often reported by projects that progress past the market authorisation stage. Trade marks are most often reported by projects that see their product adopted by the market, at least to a small scale.

Figure 17: Percentage of clinical trials associated with research council grant funding associated with a patent or registered trade mark outcome, by research council. In brackets, n = number of clinical trials associated with research council funding.

Figure 18: Percentage of research council funded projects that have reached or passed a given stage of clinical trial, and have a published patent application, granted patent or trade mark. In brackets, n = number of research council funded projects that have reached or passed that clinical trial stage.

Indirect commercialisation

Licensing

Entering a licence agreement enables anIPright owner (the licensor) to authorise another party (the licensee) to exercise some of those rights to use theIP, while the owner retains ownership and control of theIP. A patent licence allows the licensee to use the licensor’s patented invention, for example to make and sell products. A trade mark licence allows the licensee to use the licensor’s trade mark to sell products, sometimes through a franchise. Often, the licensor receives an ongoing fee from the licensee, or a ‘royalty’. Licensing of registeredIPassociated with research council grants is investigated, with the following results:

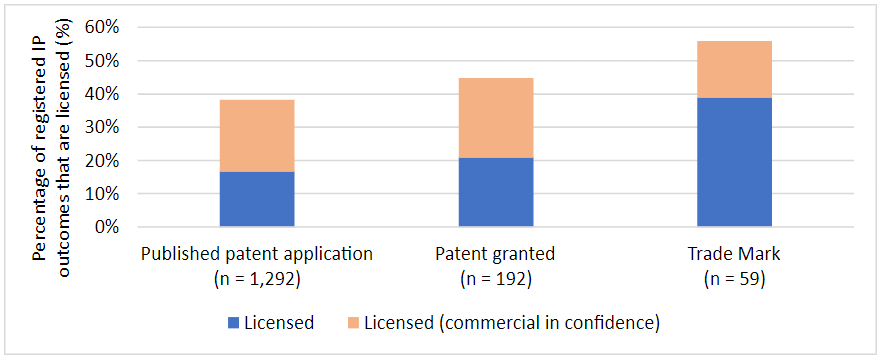

40% of all registered patent or trade mark outcomes associated with research council funding are licensed, based on information reported by grant recipients. All research councils achieved at least a quarter of registered patent or trade mark outcomes arising from their funding being licensed. The finding of highIPlicensing activity among grant recipients mirrors findings of a 2021UKRIstudy, where higher education providers in receipt ofUKRIgrants were found to generate £170m in non-software licensing revenue in 2019/20

of licenses reported, just over half are commercial agreements in confidence. These involve the signing of a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), limiting public disclosure to protect commercially sensitive information. Due to greater sensitivity around patents, they are more often associated with commercial agreements in confidence than registered trade marks (Figure 19)

trade marks are most likely to be reported by grant holders as licensed, of theIPoutcome types analysed.Trade marks are reported as licensed in over half (56%) of cases. Granted patents are reported as licensed in 45% of cases (Figure 19).

published patent applications are least frequently reported as licensed, of theIPoutcome types analysed (Figure19). It is possible to license a published patent application before it is granted. Once a patent application is granted, the applicant has the right to seek damages in respect of any infringement that took place while the application was pending, after it had been published. A party wishing to use the invention is protected from such claims by agreeing a licence before the patent application is granted.

Figure 19: Percentage of registered patent or trade mark outcomes associated with research council funded projects (2010-2020) that are licensed, byIPright. In brackets, n = number of that type of registeredIPoutcome observed.

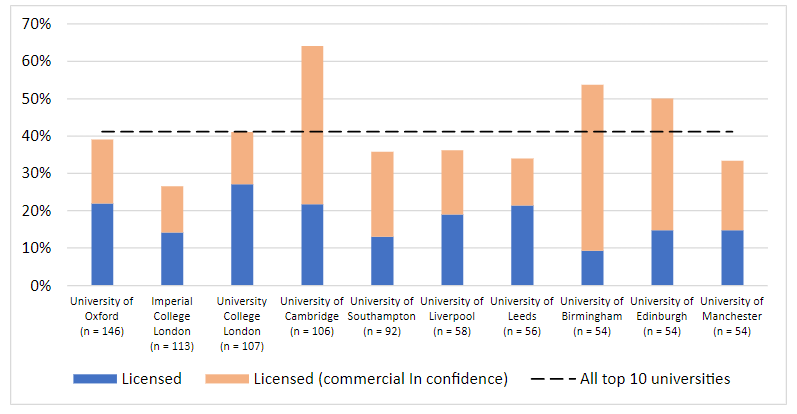

the top 10 universities (by number of registeredIPoutcomes from research council grant funding) differ greatly in licensing activity(Figure 20). The University of Cambridge and University of Birmingham have the highest share of licensed patents associated with research council grants. This result does not reflect universities’ innovation performance. Different universities have differentIPstrategies and objectives for use of theirIP, which may or may not involve licensing. Their licensing behaviour may also depend on the type ofIP, the focus of the research, and whether the university has a sectoral specialism

Figure 20: Percentage of registered patent or trade mark outcomes from research projects with a grant date starting between 2010-2020 that are licensed, by university. Universities are ordered by number of registeredIPoutcomes arising from their research council grants, 2010-2020 (n).

Collaboration with the private sector

Any cooperative activity on a project between its lead research organisation and a private sector entity may constitute private sector collaboration. This can involve the provision of expertise or guidance, access to the private organisation’s data, software, facilities or funding, help launching a good or service, and provision of PhD partnerships or internships. The Lambert model outlines the various types of agreements between universities and business collaborators, including which party has rights to any resulting IPRs.

Research councils assess collaborative research projects to ensure grant funding is compliant with UK subsidy control legislation when it is provided directly or indirectly to enterprises that engage in economic activity.

The translation of registeredIPoutcomes that arise from 2010-2020 research council grants into innovation through private sector collaboration is investigated with the following results:

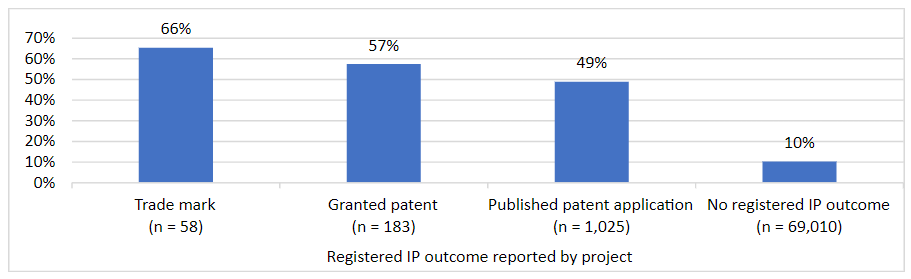

almost half (49%) of research projects that reported patent or registered trade mark outcomes also reported private sector collaboration.Research projects associated with granted patents were most likely to report a private sector collaboration. Of projects that did not report any registered patent or trade mark outcomes, 10% reported private sector collaboration

a total of 16,494 collaborations with the private sector were reported by recipients of research council grants between 2010 and 2020.Of these, 2,895 (18%) had at least one published patent application, granted patent or registered trade mark associated with the research council grant, based on self-reported data from grant recipients

recipients of research council grants between 2010 and 2020 most frequently reported collaborations with AztraZeneca(374 collaborations), GlaxoSmithKline (320 collaborations), Rolls Royce Group (151 collaborations), National Biofilms Innovation Centre (149 collaborations) and Unilever (112 collaborations)

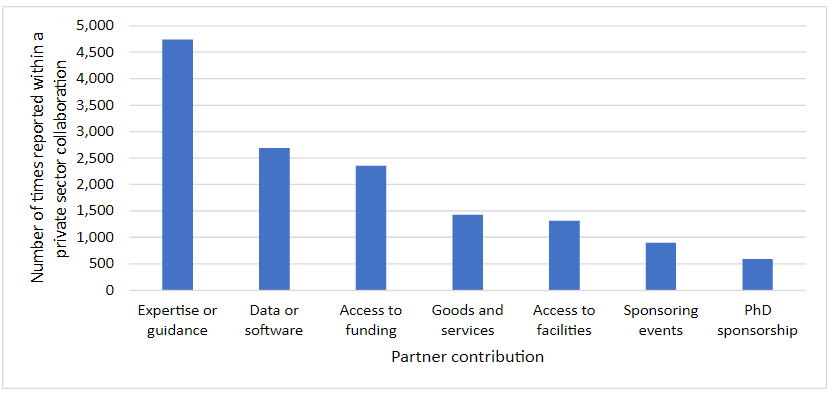

sharing of expertise, experience, knowledge and other types of guidance was the most commonly reported contribution from private companies in collaborations(Figure 21)

Figure 21: Partner contributions as reported by research council grant recipients (2010-2020), by number of times reported within a private collaboration.

projects that report a registered trade mark or granted patent are most likely to report collaboration with the private sector.66% of projects that report a registered trade mark also reported private sector collaboration, compared to 57% of projects that report a granted patent, and 49% of projects that report a published patent application (Figure 22)

Figure 22: Percentage of research council funded projects that report private sector collaboration, by whether the project reports a published patent application, granted patent or registered trade mark outcome. Includes all projects funded by the research councils, 2010-2020 (n).

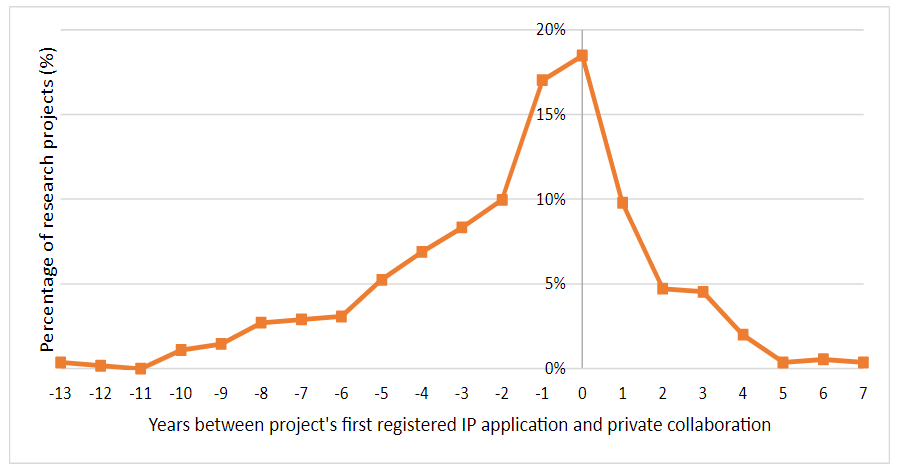

most collaborations with the private sector took place before a published patent application or trade mark registration, as was the case for 59% of research projects (Figure 23). This could be because private collaboration provides researchers with knowledge (research know-how) of industrial relevance, access to proprietary property (data, equipment, molecules, etc.) or further funding needed to develop their invention to a stage where it may be patented, or protected by a trade mark. The private organisation may also have provided a letter of supportas part of the grant application, as an industrial endorsement. A third of the patents reported by grant recipients as associated with private sector collaboration were found to have been applied for by companies in PATSTAT.

Figure 23: Percentage of research projects with a given time lag between first registered patent or trade mark filing (application year of published patent application or granted patent, or year of trade mark registration) and private collaboration. Includes all research council funded projects, 2010-2020, that led to at least one registeredIPoutcome and private collaboration.

researchers’ collaborations outside the private sector may also be key to developing uses for inventions, for example in the non-profit charity sector or in hospitals. The association between registeredIPand these types of collaborations is not assessed here

Findings and interpretation

The following broad conclusions arise from the results outlined:

Most projects receiving research council grants between 2010 and 2020 do not report a patent or registered trade mark outcome, though differences exist across grant and recipient types.

Universities with mature and well-resourced technology transfer offices are more likely to report registering patent or trade mark protection for outputs of their research council funded projects. Grant holders funded by science-focused research councils are more likely to report registering for patent protection, which may reflect differences in patentability across different specialisms of research. Grant holders that report receiving further funding from a research council or other public funding body or private organisation were more likely to report a registered patent or trade mark outcome. Regional differences in patent and trade mark registration from research council grants are observed. Research projects that completed by 2020 were more likely to report patent or trade mark outcomes; further outcomes may be expected from projects that are not yet complete. Differences in universities’IPpolicies,IPportfolio budgets, access to research facilities and equipment, and access to alternative funding sources likely also play a role.

This paper examines the role registeredIPprotection, as a policy instrument, plays in the innovation process. It does not considerIPrights protection as a measure of performance. Not all outputs of publicly funded research are compatible with patent or trade mark protection, nor is this an objective of all research council funded projects. Some researchers may prioritise publishing their findings, invalidating any subsequent patent application. Some research outputs are non-patentable, including medical treatments and diagnoses, scientific theories, mathematical methods and genetic processes. Some research outputs are not intended for commercial use, so are unlikely to be protected by a trade mark, which protects a name, slogan, logo, symbol, or other replicable feature that indicates trade origin.

The dataset is incomplete and does not take into account patents that were filed and withdrawn before publication or have not published yet. Progressing a patent application to grant stage can be costly, and some organisations may instead sell their rights to a business, leading to under-reporting in data reported to Researchfish. It also cannot be ruled out that research council funded projects not associated with a patent or trade mark outcome could have led to IPRs not analysed here, such as copyright, trade secret, design right or unregistered trade marks.

Most patents associated with research council grants are applied for within 2 years of grant receipt, though differences are observed across grant years and grant recipients.

Other factors, not analysed, could influence timing to patent following receipt of a funding grant. Grants fund research at different stages of the innovation process. Some fund early-stage research, while others fund later-stage research that is closer to being translated into innovation, such as prototyping. Consequently, the relative timing of a patent filing could reflect maturity of the research project at the time of funding. Future analysis could investigate this relationship by looking at technology readiness levels associated with patent filings.

The relative timing of a patent filing could also reflect funding received for other research projects, as research is often cumulative.

RegisteredIParising from research council funding is frequently commercialised.

Of registered patent and trade mark outcomes arising from 2010-2020 research council grant funding, 49% are reported by projects that also report private sector collaboration, 40% are reported as having been licensed, 36% are reported by projects that also report the creation of a spinout, and 14% are reported by projects that also report a clinical trial or medical product intervention. Therefore, registered patents and trade marks arising from research council funding are frequently made available for use in the market through commercialisation.

Not all patent and trade mark outcomes of research council funding are commercialised, which may reflect that:

some research council grant recipients, including universities and other higher education institutions, have charitable status. This means that any private benefit of their research must be incidental to the achievement of their charitable aims, for the public benefit. Furthermore, Research Councils adhere to the UK’s international subsidy control commitments, limiting funding of business enterprises (any entity that puts goods or services on a market). As a result, findings of commercialisation activity from research council funding may be limited

not all research council grants are intended to facilitate inventions and creations for industry use. Funding of early-stage, basic and fundamental research may facilitate knowledge exchange, including sharing of ideas, research evidence, experience and skills, which may later contribute to innovation. Furthermore, some grants may be allocated to solve particular issues, for monitoring and evaluation, or for use of existing data. Not all of these activities will be appropriate for commercialisation

several uses for inventions and creations are not considered in this paper. For example, innovation may take place through collaboration with the non-profit sector, or after the outright sale ofIP, by its acquiror or another third party

not all research projects that seek it will be successful in attracting industry interest (prospective licensees, private collaborators, or investor support for a spinout or clinical trial). Evidence has shown that inventions that have not reached prototype stage or demonstrated manufacturability and practicality in the market may be of limited interest to industry

developing an idea to commercialisation stage can be timely and cost-intensive, and further commercialisation outcomes may arise from ongoing projects and projects that receive further funding, that are not yet reflected in the data

A causal relationship between registration of published patent and trade markIPrights and commercialisation is not established through this analysis, though correlation is observed.

Despite a positive correlation being observed between theIPregistration and commercialisation of publicly funded research, one cannot conclude that patent or trade mark registration plays a causal role in the innovation process. It is possible that this correlation could reflect:

filing requirements.According to the Patents Act 1977, patentable inventions must be capable of industrial application. Commercial use is also a precondition to trade mark registration; if a registered EU or UK trade mark is not used commercially within 5 years of registration, third parties can seek to cancel it. Outputs of research not intended for industrial application, such as fundamental, basic, and theoretical research, will not fulfil patent filing requirements, and are also unlikely to be commercialised

selection effects.Grant recipients that register for patent or trade mark protection may differ from those that don’t register in ways that correlate with the commercialisation decision. For example, they may be supported by more mature or better-resourced technology transfer offices, their projects may be later stage, and the type of research may be better suited to application in industry

response bias.Grant recipients that take the time to report registered patent or trade mark outcomes through the online reporting system may also be more likely to take the time to report their commercialisation outcomes

This analysis is also unable to comment on whether the registered patent or trade mark rights reported among research council grant recipients, and their commercialisation, would have occurred in the absence of research council funding. Projects awarded research council funding may have been selected based on characteristics that correlate with their likelihood of going on to register or commercialiseIP. For example, Vanino et al (2019, find that existing patent holdings increase the probability of receiving a research council grant.

-

Previous:

-

Next: