Author:Peiyu Liu, specialized in Intellectual Property field, especially in Patent, with Qualification of Chinese Attorney and Patent Attorney. SJD Candidate in Global Intellectual Property, MSc in Data Science, LL.M in European IP Law.

Table of Contents

Research problem

Software and software-related inventions

Legal Framework for Eligibility

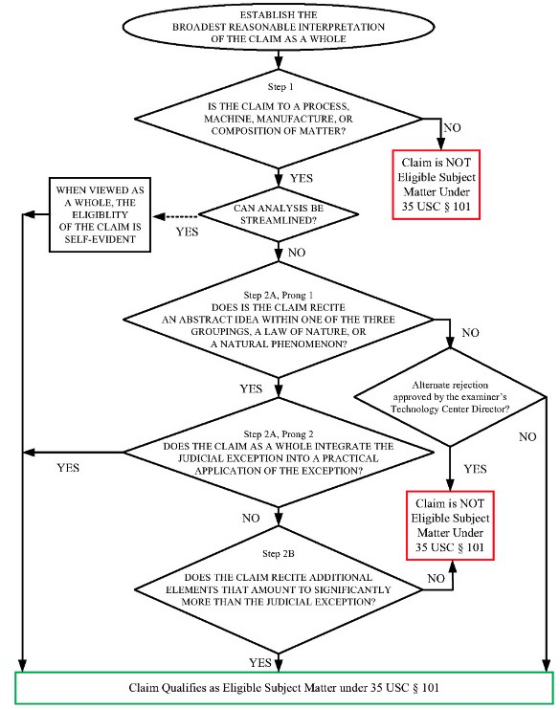

Step 1 Four Categories Test

Step 2A Judiciary Exception

Prong One

Prong Two

Step 2B Significant More

Conclusion and analysis

In the information era, software is playing an important role. People’s main daily activities involve software. To win the market competition, companies are applying for increasing software-related patents[ Patent protection for software-implemented inventions, Ania Jedrusik, WIPO MAGZINE, February 2017, paragraph 1].

Not all applications are eventually granted. Patent law imposes strict requirements to examine whether an application is patentable, including eligibility, novelty, non-obviousness, etc. Such primary requirements can be found in 35 U.S.C. § 101[ The five primary requirements for patentability are: (1) patentable subject matter, (2) utility, (3) novelty, (4) nonobviousness, and (5) enablement. This is a consensus in the industry. For such a view you can check the following articles: https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/patent access date 15 June 2023

Requirement (1) – (4) can be found in 35 U.S.C. § 101. 35 U.S.C. § 101 offers a broad requirement for patentability, and further detailed requirement of novelty and nonobviousness are provided in 35 U.S.C. § 102 and 35 U.S.C. § 103. Requirement (5) can be found in 35 U.S.C. § 112]. Before all other requirements, eligibility is the starting requirement[ Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int'l, 573 U.S. 208, 216, 110 USPQ2d 1976, 1980 (2014), at 220. “We have described the concern that drives this exclusionary principle as one of pre-emption.”].

Eligibility addresses the issue of which types of inventions are considered for patent protection. 35 U.S.C. § 101 is the statutory basis for eligibility, and the detailed rules are developed in cases. A core principle of eligibility is that abstract ideas are not eligible[ Ibid. ]. This makes software inventions in danger because software inventions are often suspected to be abstract ideas[ Abstract Ideas: The Time has Come for Congress to Address the Patentability of Software and Business Method Invention, Tanner Mort, Idaho Law Review, Volume 56, Number 3, Article 9].

This leads to the research problem of this paper:

Are software inventions eligible subject matters under current patent law?

Studying this research problem is valuable. Even though the discussion of the eligibility of software inventions has been going on for many years, there is still no pretty clear summary, especially when in 2019 the USPTO updated the section on eligibility in the MPEP[ This update mainly focused on Step 2A of the Alice-Mayo test. The Step 2A was updated into a two-prong test. At Prong Two test, MPEP added examples for abstract ideas. ]. The current papers are more of a summary of the updated section of the MPEP, without paying much attention to software patents[ For example, the paper MPEP 2106.04: ELIGIBILITY STEP 2A: WHETHER A CLAIM IS DIRECTED TO A JUDICIAL EXCEPTION, USPTO CLARIFIES ALICE/MAYO STEP 2A WITH NEW PATENT SUBJECT-MATTER ELIGIBILITY GUIDANCE, etc., are just a summary of the updated section of the MPEP, which did not pay much attention to software inventions. ]. However, this paper can do more on software inventions because the main updates in 2019 are on the evaluation of abstract ideas, more specifically, about mathematical formulas and human activities[ See the newly updated section, 2106.04(a)(2) Abstract Idea Groupings [R-07.2022]]. This part of updates affects software invention to a large extent[ I say this because software inventions are largely based on mathematical formulas and human activities. See the following contents.].

The objectives of this paper include (1) presenting the framework for eligibility examination in a detailed way; (2) developing suggestions for software inventions to make them more eligible.

Software and software-related inventions

Before we start discussing the eligibility of software inventions, we should first clarify what software is and what software-related inventions are, because the discussion is rooted in its technology.

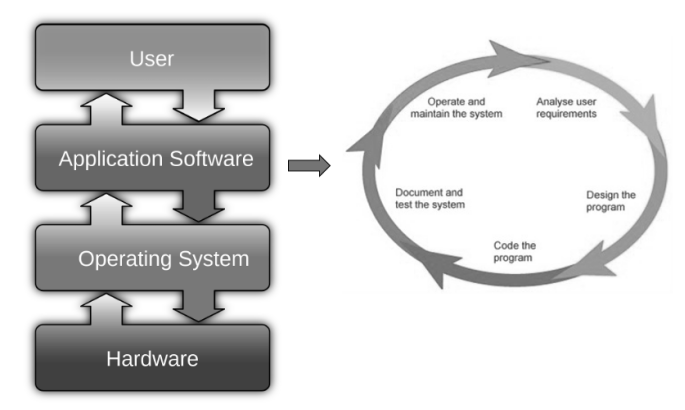

Image 1: System of Interaction and Program Development Life Cycle[ The left part of the image comes from File: Operating system placement. Offered by Wikipedia. Such content can be found on the following website https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Operating_system_placement.svg access date June 14 2023

The right part of the image comes from Programming Development Cycles, California State University. Such content can be found on https://geektechstuff.com/2022/07/22/program-development-life-cycle-pdlc/ access date June 14 2023

Note that some people believe that software is classified into two categories: application software is only one category, which performs special functions beyond the basic operation of the computer itself; system software is the other category, which provides basic functionalities that are required by users, or for other software to run properly, if at all. Such content can be found in such as Key Concepts of Computer studies, Topic B: Computer Hardware and Software, BCcampus open textbook. In the image, we included both of them, application software and operating system (which is a type of system software).

Also, not all software involve human. Here we choose the type of software involving human so that we can discuss both mathematics and human activities. ]

The whole system of interaction between software and users includes four components: users, the application software, the operating system, and hardware[ Ibid.], wherein

software is a set of computer programs and associated documentation and data[ "ISO/IEC 2382:2015". ISO. 3 September 2020. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2022. “Software includes all or part of the programs, procedures, rules, and associated documentation of an information processing system”.

Application software is a computer program that provides users with tools to accomplish a specific task.];

operating systems are essential collections of software that manage resources and provide common services for other software that runs "on top" of them[ Key Concepts of Computer studies, Topic B: Computer Hardware and Software, BCcampus open textbook.];

hardware is any physical device or equipment used in or with a computer system[ Ibid.].

Nowadays in one patent application, Applicants usually claim inventions ranging from software to implemented hardware. That is, a software-related patent has a method claim, and relevant component claims implementing the method. This tendency can be found for example in the case Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int'l, where the Applicant claimed the method for exchanging obligations, a computer system configured to carry out the method, and a computer-readable medium containing program code for performing the method.

From the technology perspective, to make software, the inventor usually starts by analyzing user requirements, then designing the program into algorithms, and finally coding the algorithms into the software[ Programming Development Cycles, California State University. Such content can be found on https://geektechstuff.com/2022/07/22/program-development-life-cycle-pdlc/ access date June 14 2023]. Therefore, software is largely based on mathematical formulas and human activities.

Bounded by the Restriction Requirement, one application can only contain one invention[ 35 U.S.C § 121: If two or more independent and distinct inventions are claimed in one application, the Director may require the application to be restricted to one of the inventions.]. If there is more than one independent claim, they must cover the same invention. In other words, the core technology of the three independent claims is the same.

Inspired by the Restriction Requirement, when applying the test of eligibility, we can choose the method claim as the focus. If the method claim fails the test of eligibility, the other claims usually fail the test, too[ See 35 USC § 101: Statutory Requirements and Four Categories of Invention, Office of Patent Legal Administration United States Patent and Trademark Office, August 2015 (although in 2019 MPEP was revised, this rule was not changed.)

“A claim whose BRI covers both statutory and non-statutory embodiments embraces subject matter that is not eligible for patent protection and therefore is directed to non-statutory subject matter. Such claims fail the first step (Step 1: NO) and should be rejected under 35 U.S.C. 101, for at least this reason.”]. This is particularly effective for software-related patents because, according to the previous analysis, the independent claims of operating systems and hardware are used only to run the methods. This approach is used in many cases, such as Alice Corp[ Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 227].

In general, the method claim is regarded as a “process”. The term “process” means process, art or method as defined in 35 U.S.C § 100(b). In case law, the term was explained as a series of acts[ NTP, Inc. v. Research in Motion, Ltd., 418 F.3d 1282, 1316, 75 USPQ2d 1763, 1791]. In fact, in all relevant cases, the method claim of software invention is regarded as a process[ For example, in the case Alice Corp., the court did not expressly define the claim into “process” category, but the court jumped the test of four categories and directly started the analysis of abstract ideas. Because the method claim can hardly be deemed as a machine or composition, dividing it into the category of “process” is the only reasonable way.

Further, in the case Bilski v. Kappos, the court held that business method could be a “process”. Although business method is not a computer program, the draft the business method claim and computer program is similar – step by step. Furthermore, in the case Bilski, when defining the term of “process”, the court specifically emphasized that “computer programs are not always unpatentable” (at 605). That is, in general, software method is considered as a process.]. The independent claims of operating systems and hardware are usually regarded as of the “machine” category[ Ibid Footnote 26.].

In fact, when the invention is software, Courts seldom consider inventions to be outside of the four categories. Among the five cases related to software eligibility heard by the Supreme Court, none of the inventions failed the four categories test.[ The cases are, Diamond v. Diehr, Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Intern., Gottschalk v. Benson, Parker v. Flook, , Funk Bros. Seed Co. v. Kalo Inoculant Co.] Further, to keep up with emerging technology, courts have tended to interpret these four categories as being broad in scope[ See Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981) at 182, or Bilski v. Kappos, 561 US 593, 130 S.Ct. at 600.].

In Step 2A the claim is examined whether it contains judiciary exceptions. 35 USC 101 does not expressly exclude any subject matters but the Supreme Court has held that Section 101 contains an implicit exception for ‘‘laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas’’[ Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 216, 110 USPQ2d at 1980 (citing Mayo, 566 US at 71, 101 USPQ2d at 1965)].

The principle behind the implicit exception is that they are basic tools of scientific and technological work[ Ibid.]. Considering that patent is a strong monopoly, allowing a patent on abstract ideas, etc. themselves is unfair to the public[ Benson, 409 U.S. at 71- 72, 175 USPQ at 676]. That shows the attitude of US patent law: patenting a judicial exception itself is ineligible but the patent could base on the judicial exception[ Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 217-18, 110 USPQ2d at 1981 (citing Mayo, 566 U.S. 66, 101 USPQ2d 1961).

“the Court has also emphasized that an invention is not considered to be ineligible for patenting simply because it involves a judicial exception.”].

Before 2019, Step 2A tests whether the claim is directed to a judicial exception[ See MPEP 2106 Patent Subject Matter Eligibility, III. SUMMARY OF ANALYSIS AND FLOWCHART]. This test was challenged in the case Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., out the reason that all inventions involve a patent-ineligible concept[ Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1335, 118 USPQ2d 1684, 1688 (Fed. Cir. 2016)

In fact, this Step was also criticized in the case Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 191-92 n.14, 209 USPQ 1, 10-11 n.14 (1981). “at some level, all inventions embody laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas”.]. In 2019, Step 2A was revised into a two-prong inquiry. We will discuss them separately.

In Prong One examiners evaluate whether the claim recites a judicial exception. The point is whether the claim recites a judicial exception or merely limitations that are based on or involve a judicial exception[ 2106.04(a)(2) Abstract Idea Groupings [R-07.2022]]. if a claim is only based on or involves an exception, it does not recite a judicial exception, and thus be eligible[ Thales Visionix, Inc. v. United States, 850 F.3d 1343, 1348-49, 121 USPQ2d 1898, 1902-03 (Fed. Cir. 2017)].

According to MPEP, when determining whether a claim recites a judicial exception, the examiner usually

(1)identifies the limitations in the claim which possibly recites a judicial exception;

(2)determines whether the identified limitations fall within at least one judicial exception[ MPEP § 2106.04(a)(2)].

It is notable that many terms, e.g., abstract idea, law of nature, etc., are recognized as judicial exceptions, but there are no bright lines between the types of exceptions. Courts have declined to define what each judicial exception is[ Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 601-602, 95 USPQ2d 1001, 1006 (2010) (citing Le Roy v. Tatham, 55 U.S. (14 How.)], and many of the concepts identified by the courts as exceptions can fall under several categories[ 2106.04 Eligibility Step 2A: Whether a Claim is Directed to a Judicial Exception [R-07.2022]]. Hence, this paper does not distinguish whether the example is abstract ideas or natural phenomena, etc., but uses “abstract idea” to refer to judicial exceptions under Step 2A.

Nonetheless, MPEP offers several examples of judicial exceptions, wherein software is specifically related to the following enumerated examples[ MPEP offers many examples under different categories of judicial exception, where the above examples related to software are actually enumerated under the category of “abstract idea”. The category of “law of nature” and “product of nature” are more related to DNA and chemical principles, which can be found in 2106.04(b) Laws of Nature, Natural Phenomena & Products of Nature [R-10.2019]. Because MPEP emphasized that there is no bright line between different categories, here we do not distinguish whether the examples are enumerated under which category, but just present the examples related to software. ]:

·Methods of organizing human activity are another example, including fundamental economic principles or practices, commercial or legal interactions, managing personal behavior or relationships or interactions between people[ MPEP § 2106.04(a)(2), subsection II].

·Mathematical concepts are an example of judicial exceptions, including mathematical relationships, mathematical formulas or equations, mathematical calculations[ MPEP § 2106.04(a)(2), subsection I

It is important to note that a mathematical concept need not be expressed in mathematical symbols, because “[w]ords used in a claim operating on data to solve a problem can serve the same purpose as a formula.” In re Grams, 888 F.2d 835, 837 and n.1, 12 USPQ2d 1824, 1826 and n.1 (Fed. Cir. 1989).].

·Mental processes is a judicial exception, which is concepts performed in the human mind[ MPEP § 2106.04(a)(2), subsection III].

As shown in Image 1, the life circle of software is tightly based on the need of consumers, so software is definitely related to methods of organizing human activity. Because the performance of a software task involves an underlying mathematical calculation or relationship, mathematical concepts and mental processes are related to software claims. In fact, when a software-related patent is suspected of reciting an abstract idea, these three categories are often first to be suspected[ In the case Thales Visionix, Inc. v. United States, McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games Am. Inc., and Enfish, etc., the claims are suspected as mathematical concepts.

In the case Alice, Bilski, and In re Marco Guldenaar Holding B.V., the claims are suspected as human activities.

In the case Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Symantec Corp., etc. the claims are suspected as mental process.].

Drafting claims in light of the enumerated examples is a more logical path today because the examiners’ focus has been shifted in past case law developments from relying on individual cases to generally applying the wide body examples[ 2106.04(a) Abstract Ideas [R-07.2022]]. However, this merely noticing the enumerated examples is not sufficient because as presented above, all inventions embody judicial exceptions at some level[ Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 191-92 n.14, 209 USPQ 1, 10-11 n.14 (1981)]. Prong 2 may help to succeed in the test of Step 2A.

If the claim is decided as reciting a judicial exception, Prong Two of Step 2A will further evaluate whether the claim as a whole integrates the exception into a practical application of that exception[ Alice, 573 U.S. at 217, 110 USPQ2d at 1981]. Put differently, whether the additional elements other than the judicial exception transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application[ Ibid. Note that the test of “transforming the nature into eligible application” is also used in Step 2B.

Also, note that the Alice/Mayo two-part test is the only test that should be used to evaluate the eligibility of claims under examination. While the machine-or-transformation test is an important clue to eligibility, it should not be used as a separate test for eligibility. Instead, it should be considered as part of the "integration" determination or "significantly more" determination articulated in the Alice/Mayo test. This is emphasized in the case Bilsiki. ]. If so, the claim is not directed to the judicial exception and therefore is eligible. If the claim does not integrate the exception into a practical application, the claim is directed to the recited judicial exception and examiners will start Step 2B.

To do Prong Two, Courts usually

·Identifying whether there are any additional elements recited in the claim beyond the judicial exception(s), and if there are additional elements

·Evaluating those additional elements individually and in combination to determine whether they integrate the exception into a practical application of the exception[ Consideration of the elements in combination is particularly important, because even if an additional element does not amount to significantly more on its own, it can still amount to significantly more when considered in combination with the other elements of the claim.].

When evaluating whether the additional elements integrate the exception into a practical application, Courts take into consideration the factors indicative of integration into a practical application. Such factors overlap with Step 2B. Here we present the factors under Step 2A Prong Two.

Step 2A Prong Two specifically excludes the factor of requiring the additional elements to represent NOT well-understood, routine, conventional activity. Accordingly, when evaluating whether a judicial exception has been integrated into a practical application, Step 2A Prong Two should ensure that all additional elements are given weight, no matter whether they are conventional. That means additional elements that represent well-understood, routine, conventional activity may integrate a recited judicial exception into a practical application.

The indicative factor that is most relevant to software inventions is

Improvements to the functioning of a computer or to any other technology or technical field[ MPEP 2106.05(a)]

If the claim aims to improve the functioning of the computer itself or any other technical fields, the additional elements are more likely to integrate the exception into a practical application[ Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 225, 110 USPQ2d 1976, 1984 (2014)].

For computer-related inventions, the improvement can be found in improving computer capabilities rather than invoking computers merely as a tool[ Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1336, 118 USPQ2d 1684, 1689 (Fed. Cir. 2016)]. According to case law, modifications on memory systems[ Visual Memory, LLC v. NVIDIA Corp., 867 F.3d 1253, 1259-60, 123 USPQ2d 1712, 1717 (Fed. Cir. 2017)], conventional Internet hyperlink protocols[ DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1258-59, 113 USPQ2d at 1106-07], distribution systems[ BASCOM Global Internet v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 827 F.3d 1341, 1350-51, 119 USPQ2d 1236, 1243 (Fed. Cir. 2016)], etc., are improvements on computer capabilities, while a typical example of using computers merely as a tool is that improvements are made by changing the executor from human to computer[ MPEP 2106.05(a) offers summaries of cases under the test of “improvements to computer functionality”. From the cases, if the improvement of computer functionality is only due to the fact that the work is done by a person to a computer, such an improvement is not enough to make the invention eligible. Instead, if the improvement is from the particular solution contained in the claim, that could make the claim eligible.].

Considering that computers are used in many industrial fields, if an invention does not improve the functionality of the computer itself, but can improve the technical field, this can also make the invention eligible[ McRO, 837 F.3d at 1316, 120 USPQ2d at 1103

Note that when evaluating whether the claim has improvement in other technical fields, the invention is not necessarily a computer-related invention. This test is for invention in any technical fields.]. For example, in McRO, the court held claimed methods of automatic lip synchronization and facial expression animation using computer-implemented rules to be patent eligible because it is directed to an improvement in computer animation and thus integrate an abstract idea into a practical application[ Ibid. ].

The core in determining the improvement to the functioning of a computer or to any other technical field is the extent to which the claim covers a particular solution to a problem or a particular way to achieve a desired outcome[ McRO, 837 F.3d at 1314-15, 120 USPQ2d at 1102-03; DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1259, 113 USPQ2d at 1107.]. An indication that the claimed invention provides an improvement could be that invention identifies a technical problem and offers a technical solution, or identifies technical improvements over the prior art[ Ibid. ].

The test of particular solution fits in essence with the case law in the above two paragraphs. When the solution is more particular, the more likely court is to find it to be a practical application of an abstract idea, and vice versa[ This is can be explained more clearly under the factor of “applying or using the judicial exception in some other meaningful way”, see the following content.].

Other indicative factors are not so relevant to software inventions[ The factor of Machine, i.e., MPEP 2106.05(b), refers to the degree to which the machine in the claim can be specifically identified. It is usually applied in the field of electronic information or other traditional machinery.

The factor of Transformation, i.e., MPEP 2106.05(c), refers to a reduction of an article ‘to a different state or thing’. It is usually applied to a process claim that does not include particular machines.

These two factors are not so relevant to software invention. The factor of MPEP 2106.05(d) and MPEP 2106.05(e) are assistance to other factors.], but they are useful to assist the evaluation of the factor “improvement”[ When evaluating the improvement factor, the considerations of that factor overlap with other considerations, specifically the particular machine consideration (see MPEP § 2106.05(b)), and the mere instructions to apply an exception consideration (see MPEP § 2106.05(f)). Thus, evaluation of those other factors may assist Courts in making a determination of whether a claim satisfies the improvement consideration.].

The factor Machine refers to the degree to which the machine in the claim can be specifically identified[ MPEP § 2106.05(b) ]. MPEP lists several considerations for the determination of factor Machine, wherein the third consideration is particularly important for software invention, which tests the extent to which the machine imposes meaningful limits on the claim[ MPEP 2106.05(b) III. WHETHER ITS INVOLVEMENT IS EXTRA-SOLUTION ACTIVITY OR A FIELD-OF-USE

The other two considerations are

I.THE PARTICULARITY OR GENERALITY OF THE ELEMENTS OF THE MACHINE OR APPARATUS

II.WHETHER THE MACHINE OR APPARATUS IMPLEMENTS THE STEPS OF THE METHOD]. Merely applying an abstract idea to a tangible machine does not make the claim eligible[ Bilski, 561 U.S. at 610, 95 USPQ2d at 1009 (citing Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 590, 198 USPQ 193, 197 (1978))]. Accordingly, merely applying a judicial exception, such as mathematical formula, on a computer, does not make the claim eligible[ This is also decided in the case Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Capital One Bank (USA), N.A., 792 F.3d 1363, 1366, 115 USPQ2d 1636, 1639 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (“An abstract idea does not become nonabstract by limiting the invention to a particular field of use or technological environment, such as the Internet [or] a computer”).]. Conversely, intangible additional elements do not doom the claims, because tangibility is not necessary for eligibility[ Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 118 USPQ2d 1684 (Fed. Cir. 2016)]. Hence, the method claim is not ineligible due to lacking tangible elements.

The factor Transformation applies to a process claim that does not include particular machines, which refers to a reduction of an article ‘to a different state or thing’[ MPEP 2106.05(c), the considerations under factor Transformation include

1. The particularity or generality of the transformation.

2. The degree to which the recited article is particular

3. The nature of the transformation in terms of the type or extent of change in state or thing.

4. The nature of the article transformed.

5. Whether the transformation is extra-solution activity or a field-of-use (i.e., the extent to which (or how) the transformation imposes meaningful limits on the execution of the claimed method steps). ]. Within this factor, if the transformation imposes meaningful limits on the execution of the claimed method, the claim is more likely regarded as eligible.

The courts have also identified limitations that did not integrate a judicial exception into a practical application. The followings are related to computer inventions:

•Merely reciting the words “apply it” or any equivalent words with the judicial exception[ MPEP § 2106.05(f)];

•Merely including instructions to implement an abstract idea on a computer[ Ibid. ];

•Adding insignificant extra-solution activity to the judicial exception, as discussed[ MPEP § 2106.05(g)];

•Generally linking the use of a judicial exception to a particular technological environment or field of use[ MPEP § 2106.05(h)].

If the claim fails Step 2A, Courts will start the test of Step 2B, where the test aims to find an “inventive concept”[ Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 217-18, 110 USPQ2d at 1981 (citing Mayo, 566 U.S. at 72-73, 101 USPQ2d at 1966)]. An “inventive concept” is furnished by an element or combination of elements that is recited in the claim in addition to the judicial exception, and is sufficient to ensure that the claim as a whole amounts to significantly more than the judicial exception itself[ Ibid.]. That is, the core of the inventive concept is “what else beyond the judicial exception”[ Ibid. “after determining that a claim is directed to a judicial exception, “we then ask, ‘[w]hat else is there in the claims before us?”].

Step 2B largely overlaps with Step 2A Prong Two, and most of factors were evaluated in Step 2A Prong Two. Thus, in Step 2B, the actual steps are[ See MPEP 2106.05 Eligibility Step 2B: Whether a Claim Amounts to Significantly More [R-07.2022], II. ELIGIBILITY STEP 2B: WHETHER THE ADDITIONAL ELEMENTS CONTRIBUTE AN “INVENTIVE CONCEPT”

The listed steps by MPEP are

• Carry over their identification of the additional element(s) in the claim from Step 2A Prong Two;

• Carry over their conclusions from Step 2A Prong Two on the considerations discussed in MPEP §§ 2106.05(a) - (c), (e) (f) and (h):

• Re-evaluate any additional element or combination of elements that was considered to be insignificant extra-solution activity per MPEP § 2106.05(g), because if such re-evaluation finds that the element is unconventional or otherwise more than what is well-understood, routine, conventional activity in the field, this finding may indicate that the additional element is no longer considered to be insignificant; and

• Evaluate whether any additional element or combination of elements are other than what is well-understood, routine, conventional activity in the field, or simply append well-understood, routine, conventional activities previously known to the industry, specified at a high level of generality, to the judicial exception, per MPEP § 2106.05(d).

Here the paper briefed it according to the above content.]:

·Carry over the identified additional elements in the claim and the conclusions from Step 2A Prong Two;

·Evaluate each additional element or combination of elements per the rule of well-understood, routine, conventional activity.

To summarize, if the claim fails the test of Step 2A, courts will further test whether the additional elements are well-understood, routine, conventional activity. If the additional elements are a specific limitation other than what is well-understood, routine and conventional in the field, then this consideration favors eligibility.

Requiring the additional elements to be not conventional does not mean the claim should be novel or non-obvious. Additional elements that are known in the art can still be unconventional or non-routine[ See, e.g., BASCOM Global Internet v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 827 F.3d 1341, 1350, 119 USPQ2d 1236, 1242 (Fed. Cir. 2016)

“The inventive concept inquiry requires more than recognizing that each claim element, by itself, was known in the art. . . . [A]n inventive concept can be found in the non-conventional and non-generic arrangement of known, conventional pieces.”]. The core of this factor is to test whether the additional elements are so unconventional that reflect an improvement to existing technology[ Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1337, 118 USPQ2d 1690 (Fed. Cir. 2016)]. The factor of Unconventional is also non-relevant to the requirement of Utility. The invention is useful does not mean it is not well-understood, and vice versa[ Genetic Techs. Ltd. v. Merial LLC, 818 F.3d 1369, 1380, 118 USPQ2d 1541, 1548 (Fed. Cir. 2016).].

In addition, to determine whether the additional elements are conventional, a factual determination is required. However, that does not mean Courts should do a prior art search. Instead, Court could rely on the general knowledge of PHOSITA. If Courts would readily find the additional elements are common use in the art according to the expertise in the art, the elements are conventional[ Ibid, at 1377 and 1546 ].

According to case law, MPEP summarized what has been recognized as conventional. The considerations related to software inventions include[ See MPEP 2106.05(d) Well-Understood, Routine, Conventional Activity [R-07.2022], II. ELEMENTS THAT THE COURTS HAVE RECOGNIZED AS WELL-UNDERSTOOD, ROUTINE, CONVENTIONAL ACTIVITY IN PARTICULAR FIELDS]

·Receiving or transmitting data over a network, e.g., using the Internet to gather data;

·Performing repetitive calculations

·Electronic recordkeeping

·Storing and retrieving information in memory

·Electronically scanning or extracting data from a physical document

·A Web browser’s back and forward button functionality

·Recording a customer’s order

·Shuffling and dealing a standard deck of cards

·Restricting public access to media by requiring a consumer to view an advertisement

·Presenting offers and gathering statistics

·Determining an estimated outcome and setting a price

·Arranging a hierarchy of groups, sorting information, eliminating less restrictive pricing information and determining the price

Note that the evaluation in Step 2B is not a weighing test, it is not important how many considerations apply from this list, but it is important to evaluate the significance of the additional elements relative to the invention[ Ibid. ].

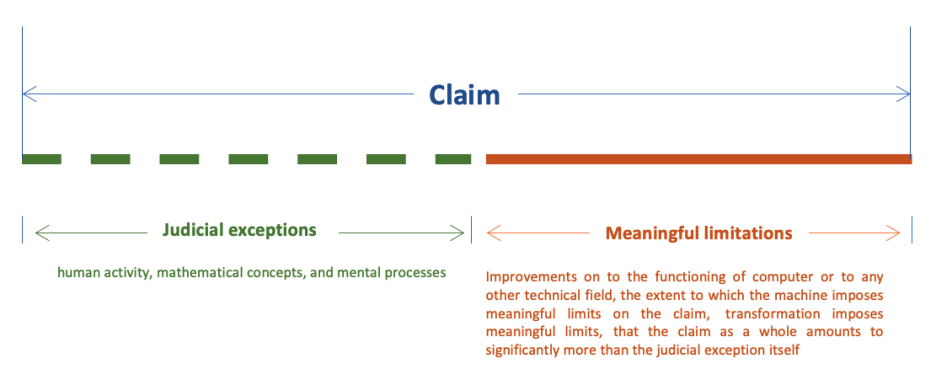

Image 3: The constitution of a claim regarding its eligibility

If the meaningful limitations make the claim much more specific than a judicial exception itself, so that granting a monopoly on the claim would not deprive too many resources from the public, the claim is more likely eligible. This may be the simplest and most straightforward conclusion that can be summarized by this paper.

Through all of the above analysis in this paper, when summarizing the framework of eligibility, the USPTO does follow the Supreme Court's interpretation of eligibility, i.e., not granting a monopoly on general scientific principles. Factors such as improvement and unconventional, which are mentioned in Step 2A and Step 2B, are only enumerations of meaningful limitations.

The enumerations are beneficial. "The standard of evaluation is subjective" has always been a criticism of the U.S. eligibility framework[ See for example Patent-Eligible Subject Matter Reform: Background and Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, Updated December 1, 2022, Chapter Criticisms of the Alice/Mayo Framework]. The USPTO's summary of the enumerations, although somewhat stereotypical, can help examiners, courts, and inventors to judge the eligibility of claims with a relatively clear standard.

Another frequent criticism of the U.S. eligibility framework is its relationship to nonobviousness[ Some scholars argue that U.S. eligibility requires so much creativity that 35 U.S.C § 101 is similar to 35 U.S.C § 103 . Other scholars contend that while creativity is mentioned in eligibility, it is a completely different requirement than nonobviousness. Such arguments can be found in The Mayo/Alice Notion of “Inventive Concept” Enables: Seeing Today’s “Preemptivity Gap”, The Scientification of Substantive Patent Law (“SPL”), and Thus Precisely Defining The Separation Line Between Patent-Eligibility and -Noneligibility of ET Cis, Sigram Schindler,

TU Berlin & TELES Patent Rights International GmbH.]. As the USPTO emphasizes, the requirement of eligibility is irrelevant to nonobviousness[ Ibid. Footnote 81.]. However, when determining eligibility, patent law does require some perception of creativity in a claim. This creativity requirement is much lower than novelty and nonobviousness, i.e., as emphasized by the USPTO, no comparison to prior art is required at all, but the claim needs to be made so unique that it does not represent a general abstract concept[ Ibid. ]. Thus, the author of this paper believes that in order for a claim to be eligible, the inventor must take at least one step toward creativity, a step that enables the claim to be a specific invention rather than a general abstract concept.

In fact, the U.S. is going through a tumultuous period with respect to eligibility determinations. Over the past decade, the U.S. patent law has undergone several significant revisions to the framework of eligibility. In the 2019 revisions, the test for Step 2A Prong Two became broadly overlapping with Step 2B, except for the unconventional requirement. To be clearer, from 2019 onward, a conventional limitation may also make abstract concepts eligible, even if it is well-known. the current framework makes the eligibility requirement more lenient compared to the previous framework. This seems to signal the attitude of U.S. patent law: there is less and less need for creativity if the limitations in the claims are sufficiently specific to make them far from abstract concepts.

Comment